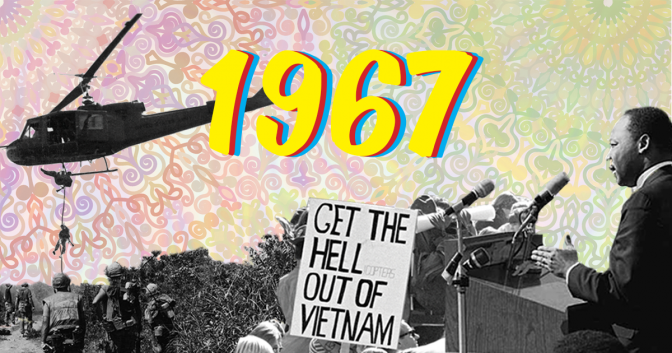

The Summer of Love Revisited: 1967, A Year of Change

The year 1967 may be remembered as the Summer of Love, but it was actually a very violent time that foreshadowed the cataclysms of 1968. It was a weird cusp of optimism and apocalypse, the hopes and dreams of the Kennedy and civil-rights era—yes, we can change the world—reaching a peak, but also the point where the doors started to close.

The Vietnam War split the county.

Looming over everything was the Vietnam War, the largest conflict the United States has been involved in since World War II. By the end of the year, there were almost 500,000 U.S. troops there, more than three times as many as in 1965.The conflict would eventually kill an estimated two million Vietnamese civilians and soldiers, and 58,000 GIs. Images of children burned alive by napalm—jellied gasoline, an incendiary weapon that sticks to skin—and soldiers with their legs blown off by booby traps permeated magazines and TV.

The war intensely divided the country. One side was viscerally repulsed by its imperialist carnage; the other despised cowardly Commies undermining our troops. This schism was much more intimate than the regional polarization of Trump-era America. Bitter arguments erupted within families, neighborhoods and schools, both about the war and the lifestyles symbolically associated with dissent.

In 1967, the antiwar movement was growing, but not yet mainstream. When the Rev. Martin Luther King declared his opposition to the war in April, calling it “a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit,” more than 150 newspapers denounced him. The civil-rights movement, after scoring a historic victory with the outlawing of segregation in 1964, faced both more complex socioeconomic issues and a vicious white backlash as it moved into the North. The previous summer, whites in Chicago had thrown bricks at a march led by King against segregated housing.

Dr. Martin Luther King addresses a large crowd in 1967.

The summer of ’67 was the fourth in a row where people in poor urban black neighborhoods rioted, burning and looting after incidents with police set off pent-up rage. In Newark, N.J., 26 people were killed in five days of rioting after a black cab driver was busted and beaten by cops on July 12. Eleven nights later, a raid on an after-hours club in Detroit sparked another five-day riot that left 43 people dead, almost 1,200 injured, and 2,500 stores burned or looted.

One more aspect of segregation fell in June, however. The Supreme Court, in its most appropriately named decision ever—Loving v. Virginia—ruled that Virginia’s law forbidding interracial marriage, under which Mildred and Richard Loving were forced to leave the state to avoid a year in prison, was un-constitutional. (The 2016 movie Loving told their story.)

If 1964-1966 was the high point of modern American liberal politics—the laws enacted in those three years included the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps and the Head Start program—1967 was the beginning of the backlash. A coalition of Republicans and segregationist Southern Democrats regained power in Congress after the November 1966 elections, foreshadowing the election of “law and order” candidate Richard Nixon as President in 1968.

Meanwhile, a countercultural movement was growing in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury, New York’s East Village, Los Angeles, Boston/Cambridge, Chicago, Detroit/Ann Arbor and Austin. Enabled by cheap rent (unimaginably cheap by today’s standards), it evolved out of the poetry-and-ecstasy quests of the ’50s Beats and the early-’60s folk-music scene’s desire for an authentic, uncommercial culture, dosed with the pop-culture flash of comics and rock’n’roll.

Sign of the the times in 1967

Free-jazz musicians—most notably John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman—sought spiritual liberation via chaos-embracing improvisation, influencing psychedelic rockers like the Grateful Dead and Janis Joplin’s band, Big Brother and the Holding Company. Soul music, the dance soundtrack to the civil-rights era, was hitting a peak in ’67 as well, with epochal records like James Brown’s “Cold Sweat” and Aretha Franklin’s “Respect.” The New York and San Francisco hippie communities also had a significant, if doubly underground, gay and lesbian presence, the fierce outcasts who planted the seeds for Stonewall and Castro Street.

“No one knew yet what the hybrid armies in the parks would turn out to mean,” feminist Marge Piercy wrote in her 1979 novel Vida. “The organizers were smoking dope and growing their hair, and the flower children, weary of being beaten by the police, were beginning to talk about the war. A great thick fog had lifted from the American landscape and people in the new sunlight were mixing colors and sounds and cultures and lifestyles.” But, she added, “Mistrust between the tribes remained.” The activists often saw the hippies as apathetic, frivolous dropouts; in turn, the hippies dismissed the activists as hectoring, uptight downers.

Several key figures had feet in both camps. Poet Allen Ginsberg spoke at antiwar protests in Berkeley and the January 1967 “Human Be-In” in San Francisco. The East Village rock band the Fugs celebrated pot and group sex while also screaming anti-war screeds (lead singer Ed Sanders had served time in jail for civil disobedience). Erstwhile civil-rights activist Abbie Hoffman was trying to organize the neighborhood’s hippies. On a stoned New Year’s Eve in his apartment, the political theater-prankster Yippies (for Youth International Party) were born.

The American pot-legalization movement emerged out of this crossover. Ginsberg was one of its first public advocates. His 1965 essay, “The Great Marijuana Hoax: First Manifesto to End the Bringdown,” hailed the “metaphysical herb” as a “useful area of mind-consciousness,” and contrasted the peacefulness of Moroccan kief-smokers with the “palpable poppycock” of prohibitionist propaganda. He was an early member of LeMar, the first formal pro-legalization organization.

Criticism of drug prohibition first entered the political mainstream, however, in Great Britain. On Feb. 12, 1967, several members of the Rolling Stones’ social circle were floating down from an LSD trip at Keith Richards’ country house when police pounded on the door. Mick Jagger was sentenced to three months in prison for possessing four amphetamine pills he’d bought legally in a drugstore in Italy, and Richards received a year for letting people use cannabis on his property. Both convictions were reversed on appeal after the august Times of London called Jagger’s sentence cultural persecution, in an editorial titled “Who Breaks a Butterfly on a Wheel?”

The anti-war movement started to pick up steam in 1967.

The Haight-Ashbury and the East Village scenes were an end as much as a beginning. The summer invasion of thousands of would-be hippies, many of them teenaged runaways, overwhelmed these counterculture communities to the point where they could barely provide people with food and places to stay. Sadly, one Haight-Ashbury predator Ed Sanders described as “scrounging for young girls using mysticism and guru babble” was a just-out-of-prison Charles Manson. The October 1967 murder of Linda Fitzpatrick and James “Groovy” Hutchinson, a Connecticut preppie and a Rhode Island working-class dropout turned East Village hippies, was another signal that all was not peace and love.

“It was a noble experiment,” Sanders wrote in his 1971 book The Family. “But there was a weakness: From the stand-point of vulnerability, the flower movement was like a valley of plump white rabbits surrounded by wounded coyotes. Sure, the ‘leaders’ were tough, some of them geniuses and great poets. But the acid-dropping middle-class children from Des Moines were rabbits.”

Still, people who were involved back then talk about an infinite sense of possibility. “I really thought love would change the world,” John Lennon said a few years later. As the ball dropped into 1968, the world was about to get much harsher.

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, subscribe to the magazine today!