Primary Colors

Every four years, Americans select a new president. But first, candidates have to go through the grueling process of primaries and caucuses.

By Erik Altieri

The 2016 presidential election is officially underway. The first ballots in the race for the White House were cast on Feb. 1 in Iowa, followed by New Hampshire eight days later.

Republican and Democratic candidates have been crisscrossing the country for many months, reaching out to voters and participating in an endless stream of media interviews. This is the heart of what is called primary season, the process through which political parties choose their candidates for the general election in November.

The presidential primaries and caucuses are a series of elections held at the state level (territories such as Puerto Rico also host their own) that serve to decide the allotment of each state’s Republican and Democratic delegates to their respective national conventions. These delegates are pledged to support specific candidates at the conventions, where the party nominees are chosen.

Primaries vs. Caucuses

A primary functions much like any other election: Voters go to polling locations and cast ballots for candidates vying to be the parties’ nominees.

The purpose of these primaries is ultimately to decide on the number of state or territory delegates allotted to each candidate and pledged to support them at each party’s national convention. Both the Democratic Party and Republican Party currently use a proportional delegate system, with each candidate getting a percentage of the state’s delegates directly based on their percentage of the vote in that state. One notable difference between the two parties is that, on the Democratic side, it’s required to achieve at least 15% of primary voters’ support to get a delegate’s backing, whereas Republicans don’t have such a threshold requirement.

Primaries come in two different forms, depending on the state. Some have open primaries, where any registered voter can vote in the primary of their choosing, either Democratic or Republican. Others are closed primaries in which in order to participate, voters must be registered members of the party whose primary they want to vote in.

Not all states have voting primaries, and instead utilize a caucus process, which is a bit more complicated. A caucus requires potential delegates to be actively involved and show support for their candidates. Caucuses are held simultaneously across a state, and voting is often done physically, by either a show of hands or by voters standing or sitting in an area of the caucus venue designated for the candidate of their choice. The potential delegates address all attendees and make the case for their candidates directly to fellow voters.

After everyone makes statements, support for each candidate is tallied. Like voting primaries, caucuses can be open or closed (some states even allow voters to register the night of the caucus, or even switch party affiliation at the caucus itself). The rules vary widely from state to state. For instance, Texas utilizes an unusual two-step process that involves both a direct voting primary and a statewide caucus.

After all localities host their primary or caucus, the next step is each party’s national convention, which the respective delegates assigned at those events all attend. This year, Republicans will convene in Cleveland July 18–21, and Democrats will gather in Philadelphia July 25–28.

Delegates allotted through the primary/caucus process are called pledged delegates, and are assigned to specific candidates. Another class of delegate is also in attendance at the conventions: unpledged delegates on the Republican side, and superdelegates on the Democratic side. These are typically current or former elected officials and other notable names in each party. Unlike the pledged delegates elected at the primaries and caucuses, these delegates are free to support any candidate they choose.

Typically, the eventual winner of the nomination is obvious before a convention even begins. But due to sheer delegate support, or because certain candidates have dropped out or conceded, it’s possible to have what’s known as a “brokered convention.” This occurs if no candidate can achieve majority delegate support at the convention after several rounds of voting. At that point, all delegates are released to support any candidate they want. It’s only happened a few times in modern political history (1924, 1932, 1948 and 1952), but is a distinct possibility this year, especially for the Republicans, whose overload of candidates could make it difficult for anyone to achieve majority support if most of them stay in the race until the convention.

February 1: Iowa Caucuses

The first state to voice its opinion on party nominees is Iowa, where both parties will hold their caucuses on Feb. 1. Iowa is often thought of as a state that can make or break a candidate by either giving their campaign a boost of momentum or showing the weakness of their organization.

Iowa’s population, however, is not very representative of American as a whole, with an overwhelmingly white electorate and large representation from extremely conservative evangelical voters. Since Iowa utilizes the caucus process, it gives candidates who may be struggling with fundraising the opportunity to chalk up a victory by maximizing face-to-face interactions and retail politics over massive ad buys and rallies.

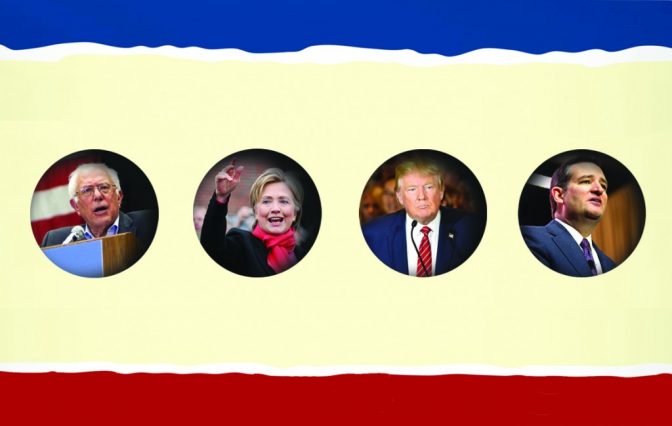

The GOP (Grand Old Party, i.e., Republican) candidates who appeal to Iowa’s staunchly conservative and religious base generally do well in caucus states. Despite his strong numbers nationally, it’s a tough state for Donald Trump to win. Senator Ted Cruz defeated him by 3% in Iowa.

Eight years ago, Hillary Clinton was the overwhelming favorite to win the Democratic nomination going into Iowa, but she suffered an embarrassing third-place finish, which drained a lot of energy out of her campaign and created the opening for Barack Obama to move into a dominant position in the race. Clinton learned valuable lessons from that Iowa debacle and invested very heavily in the Hawkeye State, building an impressive organization. Her ground game is not to be taken lightly.

Senator Bernie Sanders campaigned hard in Iowa, drawing the biggest crowds of any candidate from either party. Iowa was a true test of Sanders’ enthusiastic base vs. Clinton’s well-oiled political machine. Clinton eked out a victory by less than 1% over Sanders in Iowa.

February 9: New Hampshire Primary

The next state on the calendar, New Hampshire, has the first direct voting primary of the year. As in Iowa, Granite State voters are far more persuadable by handshaking and retail politicking, and it’s also a mostly white state that doesn’t represent the American population in its demographics. Due to the state’s small size, candidates can cover a lot of ground in a short time, and for not much money.

New Hampshire was considered a must-win (or at least a must out-perform- expectations) state for many Republican candidates. How they did in the first primary of the season can make or break candidates struggling to get out of the lower tier in the polls.

New Hampshire Republicans are much more traditional and business-oriented than those in Iowa. That’s why “establishment” Republicans like Jeb Bush, John Kasich and Chris Christie devoted most of their time and money on the New Hampshire race. A strong first-, second- or third-place finish gives candidates the fuel and momentum needed to continue on, but a solid loss may lead to a few of them dropping out of the race.

Trump was expected to take the Republican vote in New Hampshire by 10%, with Cruz, Senator Marco Rubio, Kasich, Bush and Christie trailing behind, according to fivethirtyeight.com.

For Democrats, New Hampshire is Bernie Sanders territory. All the town hall meetings and trips across the state paid off for the Vermont senator, who consistently led Clinton by double digits in the polls. Fivethirtyeight.com predicted Sanders had a 57% chance of victory with just a 2% edge over Clinton.

February 20 and 23: Nevada Caucuses

Nevada is much more diverse than Iowa and New Hampshire, with a 25% Latino population. On the Democratic side (Feb. 20 vote), Clinton is the favorite, having built a strong statewide infrastructure in 2015. However, Sanders has also been advertising and campaigning in the Silver

State and might be able to eke out a victory there.

On the GOP side (Feb. 23 vote), Cruz and Trump will probably do well, especially in Las Vegas and Reno. Expect a close race with several candidates picking up a decent number of delegates.

February 20 and 27: South Carolina Primary

South Carolina’s population is 30% black and Latino, but it’s also home to a large number of social conservatives and Tea Party voters. Trump’s opinions on ISIS and immigration seem to have resonated strongly with the base. He should win on Republican primary night (Feb. 20).

Democrats (Feb. 27 vote) in the Palmetto State heavily favor Clinton, who has very strong ties to South Carolina. The local Democratic Party apparatus and her big lead among non-white voters there give her a significant advantage over Sanders. In order to prove he’s electable, Sanders needs at least a solid showing in South Carolina. If it’s a total blowout for Clinton, as some are predicting, this could make things tough for the Sanders campaign as it moves into Super Tuesday.

March 1: Super Tuesday

Fourteen different states hold their primaries or caucuses on Super Tuesday. This is where the rubber meets the road for most candidates. Unlike the early voting states, competing on Super Tuesday requires momentum and lots of cash. With so many states deciding their delegate allotments all at once, it’s often a deciding factor for the entire primary process.

On Super Tuesday, nine states have primaries (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont and Virginia), two have Democratic and Republican caucuses (Colorado, Minnesota) and three have Republican caucuses (Alaska, North Dakota and Wyoming).

After Super Tuesday, the Republican field will be winnowed down to two or three candidates (most likely Cruz, Trump and Rubio). Sanders will need to remain competitive against Clinton or be decisively put on the sidelines. The four preceding primaries and caucuses are all about building momentum to go into Super Tuesday, and the winners and losers of these early contests will dictate who is truly in contention. The 20 primaries and caucuses through the rest of March will see leads solidified, and perhaps one Republican candidate will pull away from the pack.

Will Sanders go toe-to-toe with Clin- ton and continue the race into the later-voting states? Will the large number of Republican candidates divide the early states among themselves evenly and set the stage for a brokered convention? In politics, anything can change in a heartbeat. The run-up to primary season has been anything but boring, and some of the best is yet to come. Register to vote and participate. The future of the country is at stake.

Erik Altieri is President of The Agenda Project and the former Communications Director for NORML.