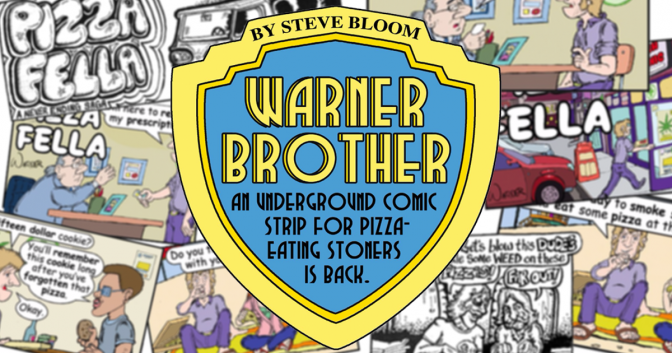

«Pizza Fella’: The Underground Comic Strip for Stoners is Back

If you look up Neal Warner on IMDb, you’ll find references to animated films and TV shows he’s worked on, like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Rugrats and Heavy Metal, but there’s no mention of his 1970s underground comic strip, Pizza Fella.

“It was from and about Los Angeles in the early ’70s, and is where Pizza Fella made its debut in late 1971,” the Hollywood native tells me. “Funny thing about 1971, not only did Pizza Fella debut in L.A. Comics #1, but Cheech & Chong’s first album came out then, and some high school students coined the term ‘420.’”

Drawn in black and white, the original Pizza Fella strip (at left) had a distinct Art Crumb look. “What I got from the underground comix style was freedom to lay out a page in creative ways—not just a series of panels—getting more abstract with the backgrounds, and incorporating the dialogue text as part of the design,” Warner explains.

Drawn in black and white, the original Pizza Fella strip (at left) had a distinct Art Crumb look. “What I got from the underground comix style was freedom to lay out a page in creative ways—not just a series of panels—getting more abstract with the backgrounds, and incorporating the dialogue text as part of the design,” Warner explains.

“This was a major element in psychedelic posters, and I discovered that it made it a lot more difficult for editors to censor or change your text. One of the stylistic elements of guys like Crumb was using contour lines that indicate shadows and highlights to suggest a rounded quality to the characters. Crumb’s characters always appeared rubbery to me. Storywise, I really liked Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, one of the few underground comix where the characters were the stars rather than the artist.

“I was never a big fan of regular comic books,” he adds. “I liked underground comix and Mad Magazine, which I’d buy for the artists and writers, rather than for a particular character.”

Warner’s first comic, Mother Gross, was published in 1970 when he was still in high school. “Although I was published twice a month for about two years—until I left L.A. to go to school in San Diego—only about a half dozen of the comics were Pizza Fella,” Warner notes. “There was a late-night TV show I watched in the late ’60s called Fright Night. Larry Vincent, who played a character called Sinister Seymour, hosted it. During the segments before and after the commercial breaks, Seymour would make fun of bad horror films, and, as a recurring gag, he would use a pay phone on the set to try and order food from Pizza Fella, a spoof on the popular pizza delivery chain Pizza Man. Although you could never hear Pizza Fella’s side of the phone conversation, you could tell he was funny and probably a stoner.

“A lot of people staying up past midnight watching bad horror movies and ordering pizza were also probably stoners. When the offer to create a six-page comic for L.A. Comics came about, I figured if I made it about Pizza Fella, a lot of my target audience—stoners in Los Angeles—would already be familiar with the character. It seemed to have worked.”Warner was subsequently hired by Ralph Bakshi, director of Fritz the Cat, who Warner recalls “had an affinity for underground cartoonists.” After that, he worked for Fred Wolf Films, the animation studio, “for the next 30 years. I’ve worked at every major animation studio in L.A. over the years, on both TV series and movies. I worked on Justice League for Warner Brothers this year, and a few years ago I worked on the last season of Brickleberry.”

Recently, Warner decided to get back to his underground comix roots by reviving Pizza Fella for the medical-cannabis generation. “I wanted him to reflect the new and changing attitudes about marijuana,” Warner says. “As a joke, which probably only I get, the strip now looks less like an underground comic and more like the comics in the Sunday L.A. Times. In my mind, the original Pizza Fella back in the ’70s was my age, and this new one is not the same guy, but rather his son. Pizza Fella now spends a lot more time with lady friends, and I think this is because he’s not just a pizza delivery guy, but the son of the man who now owns the pizza company, and he thinks that someday it will all be his.”

Warner, who lives in Valencia, Calif. with his wife and three sons, surprisingly is not sold on marijuana legalization, which Californians will have the opportunity to vote for in November. “I do feel the genie is out of the bottle, and even if legalization fails, it’s not as if I won’t be able to get high like I’ve been doing all along since I was 17 years old—when I felt that someday the baby boomers will be in charge and then we’ll legalize marijuana,” he remarks wryly. “Once we did get in charge, we still didn’t want it legal because we were raising our kids and didn’t want them to have easy access to it, but now our kids are adults, we’re getting old and someday soon it will be too difficult for us to go out on the streets to score. Growing old, sick and dying is not something we’ll want to do straight.”

Warner, who lives in Valencia, Calif. with his wife and three sons, surprisingly is not sold on marijuana legalization, which Californians will have the opportunity to vote for in November. “I do feel the genie is out of the bottle, and even if legalization fails, it’s not as if I won’t be able to get high like I’ve been doing all along since I was 17 years old—when I felt that someday the baby boomers will be in charge and then we’ll legalize marijuana,” he remarks wryly. “Once we did get in charge, we still didn’t want it legal because we were raising our kids and didn’t want them to have easy access to it, but now our kids are adults, we’re getting old and someday soon it will be too difficult for us to go out on the streets to score. Growing old, sick and dying is not something we’ll want to do straight.”

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, subscribe to the magazine today!