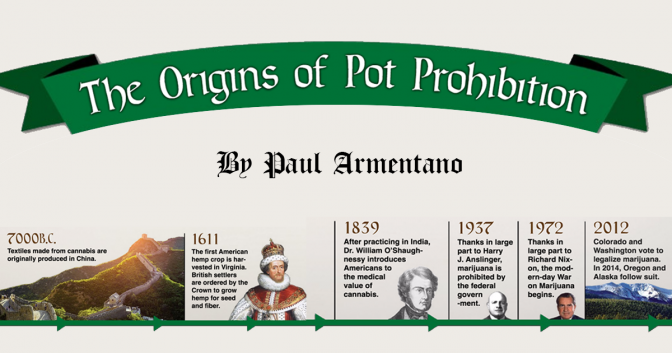

The Origins of Pot Prohibition

Humans have cultivated and consumed the cannabis plant since virtually the beginning of recorded history. Cannabis-based textiles dating to 7000 B.C. have been recovered in northern China, and the plant’s recorded use as a medicinal and euphoric agent dates back nearly as far. Modern cultures continue to use cannabis for these same purposes, despite a virtually worldwide ban on its cultivation and use.

Americans lived in harmony with the marijuana plant from the Colonial era until just after the turn of the 20th century. Some historians believe that settlers harvested America’s first hemp crop in 1611 near Jamestown, Va. Shortly thereafter, the British Crown ordered colonists to engage in wide-scale hemp cultivation—a practice that farmers continued in earnest for the next 300 years.

Physician William O’Shaughnessy introduced Americans to the herb’s medicinal value in the mid-1800s. While practicing in India, O’Shaughnessy began documenting the medical uses of cannabis, which he introduced into Western medicine in 1839. By the 1850s, oral cannabis extracts became available in U.S. pharmacies, where they remained a medical staple for the next 60 years. Despite the drug’s widespread availability as an herbal remedy, reports of recreational abuses of cannabis were virtually nonexistent in the literature of that time. In fact, during congressional hearings leading up to the passage of the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914—the nation’s first federal anti-drug act—witnesses argued against prohibiting cannabis, stating that “as a habit-forming drug, its use is almost nil.” Congress heeded their advice and wisely excluded cannabis from the statute.

But reefer sanity quickly gave way to reefer madness. Over the following years, legislatures in several U.S. states, including California, Colorado, Maine and Massachusetts, outlawed the plant’s possession—often citing lurid, unsubstantiated claims about the weed’s adverse effects among predominantly poor and ethnic populations. By the late 1920s, newspaper headlines and editorials sensationalizing the alleged dangers of pot began sweeping the nation. Respected publications like the New York Times proclaimed that marijuana intoxication caused incurable insanity, while law enforcement personnel alleged that pot use triggered wanton sexual desires and irreparably destroyed the brain.

“If continued, the inevitable result is insanity, which those familiar with it describe as absolutely incurable, and, without exception, ending in death,” declared a 1933 editorial in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. Few among the public, and even fewer elected officials, disputed these claims.By 1937, members of Congress—which had resisted efforts to clamp down on the drug some two decades earlier—were poised to take action. Following the lead of the states, most of which had now banned the plant’s possession and use, federal politicians readied to enact their own pot prohibition.

“If continued, the inevitable result is insanity, which those familiar with it describe as absolutely incurable, and, without exception, ending in death,” declared a 1933 editorial in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. Few among the public, and even fewer elected officials, disputed these claims.By 1937, members of Congress—which had resisted efforts to clamp down on the drug some two decades earlier—were poised to take action. Following the lead of the states, most of which had now banned the plant’s possession and use, federal politicians readied to enact their own pot prohibition.

On April 14, 1937, Rep. Robert L. Doughton of North Carolina introduced House Bill 6385. The measure sought to stamp out recreational use of marijuana by imposing a prohibitive federal tax on the plant’s cultivation and possession. Members of Congress held only two hearings to debate the merits of the bill. The federal government’s chief witness during the hearings was Harry J. Anslinger, a law-and-order evangelist and director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Anslinger’s anti-pot zealotry was legendary.

Under oath, Anslinger told members of Congress, “This drug is entirely the monster Hyde, the harmful effect of which cannot be measured,” and called for its blanket criminalization. Over objections from the American Medical Association, which testified vociferously against the proposed federal ban, members of the House and Senate over-whelmingly approved the measure. That August, President Franklin Roosevelt promptly signed the legislation into law. On Oct. 1, 1937, the Marihuana Tax Act officially took effect, thus setting in motion the federal prohibition that continues unabated today.

The Shafer Commission and the Advent of Decriminalization

While federal pot prohibition began with the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act, the plant’s present-day illicit status is a consequence of its classification under the U.S. Controlled Substances Act. (The 1937 law was ultimately ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1969.) Of the five drug categories established by the CSA, politicians placed cannabis in the most prohibitive category, Schedule I. But this decision was intended only to be temporary. That’s because the act called for the creation of a federally appointed commission to study all aspects of the cannabis plant, its use and its consumers. The presumption was that lawmakers would revisit pot’s restrictive status once this blue-ribbon commission completed its work and reported its findings back to Congress. But things didn’t work out as planned.

After nearly two years of scientific study, Congress’ marijuana commission —known as the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (aka the Shafer Commission, named after its chairperson, Pennsylvania Governor Raymond P. Shafer)—completed its investigation. The multimillion-dollar fact-finding mission, titled “Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding,” was trumpeted upon its completion as “the most comprehensive study of marihuana ever made in the United States.”

The commission issued its report to Congress and to President Richard Nixon on March 22, 1972. In unambiguous language, it rebutted virtually every negative claim made about the herb’s alleged dangers. Specifically, the commission concluded that pot was not a so-called “gateway drug”; that its use was not associated with violence or aggressive activity; and that its consumption was not physiologically or psychologically detrimental to health.“Neither the marihuana user nor the drug itself can be said to constitute a danger to public safety,” it concluded. “Therefore, the Commission recommends… [that the] possession of marijuana for personal use no longer be an offense, [and that the] casual distribution of small amounts of marihuana for no remuneration, or insignificant remuneration, no longer be an offense.”

This public-policy recommendation, known as “decriminalization,” stipulated that those who possess or dispense personal-use quantities of the herb should no longer face arrest or jail time; instead, minor pot violations would be punishable by the payment of a small fine. By contrast, large-scale dealers and traffickers would continue to face criminal sanctions, and the plant itself would remain contraband.

The commission’s findings and recommendations should have triggered a serious review of federal marijuana policy and penalties. That didn’t happen. Instead, President Nixon vehemently rejected the commission’s conclusions, and the federal government doubled down on demonizing pot. As had been the case more than three decades earlier, science and reason held little sway with federal policymakers, who instead chose to embrace cultural and racial stereotypes over facts and evidence. Flexing the muscle of the newly formed anti-crime super-agency, the Drug Enforcement Administration, Nixon declared that his administration was launching the first official “war” on drugs. Public enemy No. 1 in this battle was marijuana.

Although federal officials ignored the Shafer Commission’s call to decriminalize pot, state politicians took notice. In 1973, Oregon became the first U.S. state to amend its marijuana laws in a manner that followed the commission’s recommendations. Over the following years, 10 more states—Alaska, California, Colorado, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina and Ohio—decriminalized marijuana possession offenses. In each of these states, minor marijuana offenders face fines, but no longer risk prison time (and, in most cases, they also no longer face a criminal record).

These policy changes allowed states to free up judicial and prosecutorial resources to focus on more serious crimes, and did not result in increased marijuana use among young people or the general public. In fact, the federal government’s own review of statewide decriminalization policies (“Marijuana Legalization: The Impact on Youth 1976 –1980”) concluded: “[D]ecriminalization has had virtually no effect either on marijuana use or on related attitudes and beliefs about marijuana use among American young people. The data show no evidence of any increase, relative to the control states, in the proportion of the age group whoever tried marijuana. In fact, both groups of experimental states showed a small, cumulative net decline in annual prevalence after decriminalization.”

The popularity of decriminalization waned in the ‘80s—a decade that marked the zenith of drug-war fervor. Predictably, no additional states passed cannabis decriminalization laws during this time period. Yet, despite the advent of “Just Say No,” advocates managed to hold the line. Throughout the Reagan/Bush era, no state legislature repealed their decriminalization laws.

By the late ‘90s, state politicians began once again to consider the benefits of decriminalizing pot. In 2001, Nevada became the first state in over two decades to reduce marijuana possession penalties to a fine-only offense. In recent years, several additional states have enacted similar changes in law, reducing minor pot possession offenses from criminal misdemeanors to civil infractions punishable by a fine only—no arrest, no jail and no criminal record.

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, consider subscribing today!