New York’s Compassionate Care Act Challenged

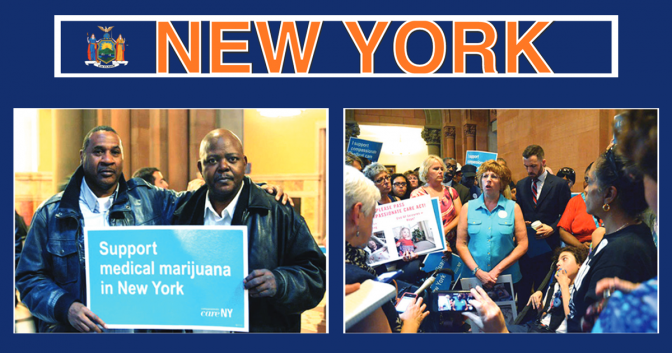

In June 2014, New York became the 23rd state to legalize medical marijuana. Two years later, the medical program, which went into effect this past January, is the target of broad criticism, chided as overly restrictive and one of the most un-workable programs in the country. Now, legislators, activists and industry professionals are trying to fix it.

“There’s a lot of interest in seeing the program succeed,” says Steve Stallmer, spokesman for Etain Health, one of New York’s five companies registered to grow, manufacture and dispense cannabis medicine. “It’s just a matter of what steps these legislators take to help improve it.”

Manhattan Assemblyman Richard Gottfried, lead sponsor of New York’s Compassionate Care Act, has introduced eight bills to amend the current program. Gottfried has championed the cause since 1997, when he proposed legislation in New York in response to California’s medical marijuana (MMJ) law, Prop 215, which passed in 1996. Gottfried spent nearly 17 years trying to move his bill through the state assembly and senate, only for it to finally arrive in 2014 at the desk of Governor Andrew Cuomo, who demanded amendments that severely pared down the legislation’s ability to serve patients in need.

In its current form, New York’s MMJ program allows just five registered organizations (ROs) to grow and manufacture cannabis products and operate 20 dispensaries (four per RO) throughout the state’s 54,556 square miles. Only 10 “severe, debilitating or life-threatening” conditions are covered under the law: cancer, HIV/AIDS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, inflammatory bowel disease, neuropathies, Huntington’s dis-ease and damage to nervous tissue of the spinal cord. The law does not allow smoking whole-plant cannabis, or even eating medicated edibles.

The few products allowed under the Compassionate Care Act are meant to mimic the look and feel of pharmaceutical medicine: capsules, vaporizable oils, dissolvable strips, patches and tinctures. Limited combinations of cannabinoids are available in these forms. Each dispensary carries dis-tinct products that are THC-dominant, CBD-dominant and 1:1 balanced be-tween THC and CBD.

By the end of July, 7,000 patients had received MMJ recommendations from the 675 physicians (of the state’s 80,000) who have registered with the program and completed a four-hour training course.

Before the program even went into effect on Jan. 7, Gottfried and patient advocates were already pushing for re-forms. Included in Gottfried’s package of bills are proposals to expand the number of ROs and the list of treatable conditions; allow patients to smoke whole-plant cannabis; and eliminate the requirement that the same company must both grow and sell the cannabis.

On May 25, the New York State Assembly passed two bills meant to improve patient access to MMJ. “Today, patients are struggling to find healthcare providers authorized to prescribe medical marijuana due to changes to the bill made by the governor in order to secure his support,” Gottfried stated. “These bills bring the law closer to the original bill as passed by the assembly and supported by patients and their doctors.”

One of these bills, A9510, sponsored by Gottfried, authorizes nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) to recommend MMJ to eligible patients. “New York law allows NPs and PAs to prescribe the strongest and most dangerous controlled substances, but not medical marijuana,” Gottfried added. “Patients in need should not be denied access to critical medication just because they’re treated by a PA or NP. There are tens of thousands of New Yorkers who are not able to get access.”

The other bill, A10123, sponsored by Assemblywoman Crystal Peoples- Stokes, would require the contact information of all doctors registered with the program to be available on the New York State Health Department’s website. Bewilderingly, the list of registered physicians has not been made public, and, as a result, patients are forced to cold-call doctors in order to find one willing and able to recommend MMJ.

“I believe that current law—both the Compassionate Care Act and the Freedom of Information Law—requires that this list be public, as was the legislative intent,” Gottfried explained. “But apparently, it needs to be spelled out.”

Stallmer would like to see more conditions added to the list of eligible illnesses, such as PTSD and chronic pain; a hike in the number of dispensaries from 20 to 40; restrictions lifted on the kind of cannabis that’s available to patients; and for ROs to be able to advertise and market their services, which they’re currently not allowed to do.

Expanding the conditions list would help the ROs reach more people by in-creasing the “pool of patients,” Stallmer says. “The problem is the lack of patients who’ve signed up, and the lack of doctors who’ve taken the course.”

Still in its infancy, the program is growing, albeit at a slow rate. “Every month we’re serving more patients,” says Ari Hoffnung, CEO of Vireo Health, one of the state’s five ROs. “We want to have locations in less populated areas, and delivery services—that’s something we would like to explore. Some of our patients are homebound, and find it challenging to get to the dispensaries.”

Legal MMJ prices are set by the state; the quantity used and expense varies among patients. “A young girl who’s suffering from neurological disease will have one dosage, and a grown man going through chemo will have another,” Hoffnung says. Significantly, because this medicine is not covered by insurance, patients must pay out of pocket.

Some patients don’t take prescription medications that are given to them free of charge, but cannabis patients shell out copious amounts of money, and come back for more.

“That’s a great test to see if a medicine is actually working,” says Dr. Stephen Dahmer, Chief Medical Officer at Vireo. “I’m on the phone all day speaking with physicians, discussing medical cannabis as a therapeutic option. The interest is high, but there’s a long way to go.”

Update: On Aug. 29, the Health Department approved the following changes in the Compassionate Care Act:

• Delivery services for patients too ill to travel to a dispensary.

• Nurse practitioners are allowed to certify patients, in addition to doctors.

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, consider subscribing today!