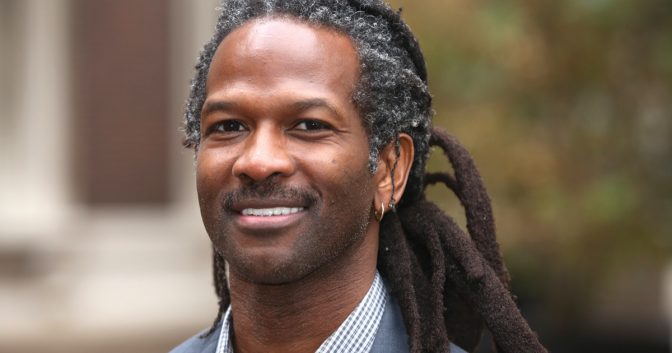

Dr. Carl Hart on Moving Beyond Cannabis Legalization

On Sept. 22, before an enthusiastically cheering Alabama crowd, Donald Trump declared in animated fashion, “Get that son of bitch off the field!” What would inspire such offensive language from a United States President? Was he angry with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un over his nuclear-weapons program? Or perhaps his ire was aimed at Russian President Vladimir Putin for interfering in the 2016 U.S. election?

Nope. It wasn’t any of the above. It turns out Trump was angry with Colin Kaepernick and other National Football League players who have silently protested—by refusing to stand for the national anthem in response to racial injustices perpetrated by police officers who are rarely held accountable. Like many Americans, I feel Trump’s actions were beneath the office that he holds. Further, rather than inflaming racial tensions, Trump should use the vast resources available to him to fight the very injustices that Kaepernick and others have highlighted.

Philando Castile was killed by an officer in 2016. The officer was acquitted in 2017.

Eradicating the harm caused by racism in drug-law enforcement would be one good starting place. Last year, 653,000 Americans were arrested for simply possessing cannabis. Even though this number is down from its peak (more than 850,000 in 2010), at the state level, black people are four times more likely to be arrested for cannabis than their white counterparts. At the federal level, Latinos represent two-thirds of the individuals arrested for cannabis violations. This is despite the fact that blacks, Latinos and whites all use the drug at similar rates, and they all tend to purchase the drug from individuals within their own racial group. This is an unambiguous example of racism in drug law enforcement.

What’s worse, in these encounters with police, too often the black person ends up dead. There have been several recent cases during which officers cited the fictitious dangers posed by cannabis to justify their deadly actions. On July 6, 2016, in the St. Paul suburb of Falcon Heights, Minn., officer Jeronimo Yanez shot and killed Philando Castile, a black, defenseless motorist, as his girlfriend and young daughter watched helplessly. The smell of cannabis, Yanez claimed, constituted an apparent imminent danger. This past June, he was acquitted of manslaughter.

Of course, this wasn’t the first time (nor will it be the last) a police officer has cited the “cannabis makes black people homicidal” defense to justify these deadly interactions. Michael Brown, of Ferguson, Mo., in 2014 and Keith Lamont Scott, of Charlotte, N.C., in 2016 were both killed by police who used some version of this bogus defense. Both officers were acquitted.

Ramarley Graham was shot and killed by a New York police officer in 2012.

Ramarley Graham (New York, 2012), Trayvon Martin (Sanford, Fla., 2012), Rumain Brisbon (Phoenix, 2014) and Sandra Bland (Prairie View, Tex., 2015) all also had their lives cut short as a result of an interaction with law enforcement (or a proxy) initiated under the pretense of suspicion of cannabis use. One way to decrease these deadly interactions is to make cannabis legally available for adult consumption. Indeed, to date, eight states have passed such legislation. In Colorado, where since 2014 the law has permitted adults to use cannabis recreationally, they’ve seen a dramatic decrease in the number of cannabis arrests. This number has dropped by more than 50% for some demographic groups. Similar findings have been observed in Washington State and in the District of Columbia.

Even after cannabis legalization, however, the racial disparities in arrests still persist. For example, black Coloradans remain three times more likely to be busted for cannabis violations than white Coloradans. The point is that changing marijuana laws alone is helpful—because it decreases potentially hostile interactions between blacks and the police—but is insufficient for correcting racial injustices that are deeply embedded in our society. In other words, it would be naïve to think that changing cannabis policy alone will alter the racist behavior of some Americans.

Sandra Bland allegedly hung herself in jail after being arrested in 2015.

California’s Proposition 64, which legalized recreational cannabis for adults in 2016, was touted as a racial-justice initiative that redresses previous discrimination in marijuana-law enforcement. Indeed, Prop 64 states that tax revenues generated from cannabis sales will be directed toward “communities disproportionately affected by past federal and state drug policies.” But, as Seattle University law professor Steven Bender eloquently noted, “The Proposition language neither identifies those communities nor overtly links their identity to racialized populations or racialized enforcement bias.” Stated another way, Prop 64 is not a racial-justice initiative. Nor are any of the other referendums that have legalized cannabis.

So then, what is needed? In addition to legalizing cannabis at the federal level, law-enforcement agencies should be required to report and justify cannabis-arrest data. If racial discrimination is detected, then immediate consequences should be implemented. Consequences could include, but not be limited to, judicial oversight for the violating law-enforcement agency and/or a decrease in that agency’s budget. It’s remarkable how quickly behavior changes when appropriate and immediate consequences are imposed.

Changing marijuana laws decreases potentially hostile interactions between blacks and the police, but it is insufficient for correcting racial injustices that are deeply embedded in our society.

Changing marijuana laws decreases potentially hostile interactions between blacks and the police, but it is insufficient for correcting racial injustices that are deeply embedded in our society.

Back in the 1930s, when there was little scientific evidence investigating the effects of cannabis on human behavior, we were vulnerable to exaggerated anecdotal accounts of its supposed tendency to induce aggression and violence. Law-enforcement types like Harry J. Anslinger, commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, routinely recounted gruesome stories such as this one:

“[P]olice found a youth… with an ax he had killed his father, mother, two brothers and a sister… he had become crazed from smoking marijuana.” These fabrications were widely disseminated, facilitating passage of draconian policies, racial discrimination and incalculable human misery.

More than 80 years later, I’ve given thousands of doses of cannabis to people as a part of my research and have never seen a research participant become violent or aggressive while under the influence of the drug. Hence, the reefer-madness myth should be dispensed with immediately. So too should politicians who encourage racism and policies that have the same effect.

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, subscribe to the magazine today!