Advocates and Legislators Reach Compromise on Controversial Marijuana Initiative in Utah

Mormons with Mexicans in Northern Mexico, 1908

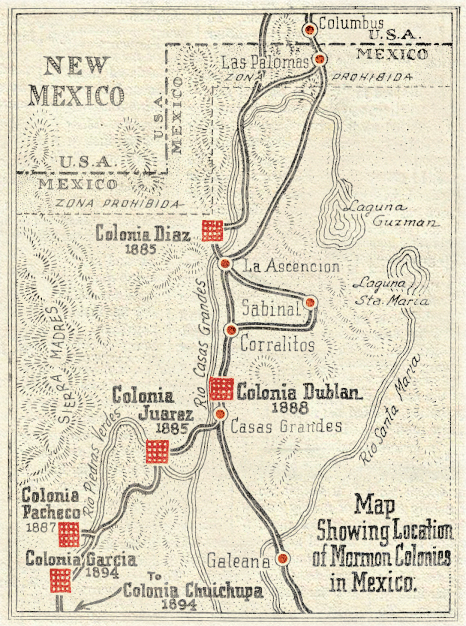

In 1885, the prophet and president of the Mormon Church, John Taylor, purchased about 100,000 acres of land in Mexico—in Chihuahua and Sonora, to be exact, some 200 miles south of the US border. More than 300 polygamous Mormon families from Utah migrated south to settle the land and to proselytize (even today you see the traveling twosomes of fresh-faced young men in their white shirts, ties and black name tags) and, many theorize, to preserve the practice of polygamy.

At the time, Mormon polygamists were being jailed and having their property seized. Utah itself was denied statehood by the federal government to halt the practice. Former presidential candidate Mitt Romney is descended from the Mexican settlements; his father, George, and grandfather, Marion, were born in Colonia Dublán, Mexico, in 1907.

But in 1910, many who had settled in northern Mexico began an exodus back to Utah due to anti-American sentiment fueled by the Mexican Revolution. Some say they returned with a local plant introduced by the natives: cannabis.

The Mormon Church, formally known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS), were and still are infamous for their teetotaler ways and as abstainers of vices of all kinds; hence, they didn’t look kindly on the brethren partaking of the plant, viewing it as a violation of Mormon scripture from the “Doctrine and Covenants,” section 89 (D&C 89), commonly referred to as the “Word of Wisdom.”

Mormon Church founder Joseph Smith

Church founder and prophet Joseph Smith wrote D&C 89 at the strong urging of his wife, Emma, who was tired of Smith’s friends gathering in their home and spitting tobacco on the floor. But Smith went far beyond forbidding tobacco; D&C 89 also bans the use of wine, coffee, tea and liquor. And it promises that those who follow the doctrine will receive health, protection, knowledge and wisdom from God.

So when the settlers returned from Mexico with marijuana in hand, church leadership urged the legislature to officially outlaw cannabis in 1915. Four years earlier, Massachusetts became the first state to prohibit marijuana, followed by California, Indiana, Maine and Wyoming in 1913; New York in 1914; Utah and Vermont in 2015; and Colorado and Nevada in 1917.

19th Century map of Mormon colonies in Mexico

This version of events seems to have first appeared in 1995, when a University of Southern California law professor, Charles Whitebread, floated his theory in a speech to the California Judges Association, “The History of Non-Medical Use of Drugs in the United States.” Riddled with historical and cultural inaccuracies, Whitebread said that he “had help from some people in Salt Lake City associated with the Mormon Church and the Mormon National Tabernacle in Washington,” which does not exist.

At the instruction of Smith’s successor, Brigham Young, 19th-century Mormons became incredibly self-sufficient, raising their own cotton, flax, silk and, yes, hemp to limit interactions with non-Mormons. In the Journal of Discourses, a pioneer-era magazine written by church leadership in the late-1800s, leaders advised members, “We must make our own woolen, flax, hemp and cotton goods or we must go naked.”

Nonetheless, Whitebread drew the line straight from Mexico to Salt Lake City and blamed the cannabis ban on the morals of the church. Mormon historian Ardis E. Parshall challenges Whitebread’s logic in her 2009 article, “The Great Mormon Marijuana Myth,” a comprehensive, if dense, takedown citing LDS conference talks, newspaper editorials and even arrest records, making Whitebread’s explanation much less tidy.

Former presidential candidate Mitt Romney is descended from the Mexican settlements; his father, George, and grandfather, Marion, were born in Colonia Dublán, Mexico, in 1907.

“There is no hint whatsoever that Utah’s law—which you now see did not specifically target marijuana or even show particular awareness of marijuana, but merely incorporated the language used by other entities to name marijuana among a whole host of regulated drugs—was spurred by religious concerns,” Parshall wrote.

Parshall’s contention that religion had nothing to do with the original 1915 ban, however, does not seem to hold much water today. In November, Utahans will have the opportunity to vote on Prop 2, a.k.a. the Utah Medical Cannabis Act—a ballot initiative that, if it passes, will blow open Utah’s legal cannabis landscape.

LDS leadership has taken a position against Prop 2, even going so far as to commission Salt Lake City law firm Kirton McConkie to conduct a legal analysis of its implications. In May, based on the firm’s findings, the church concluded that “serious adverse consequences could follow if it were adopted,” citing “grave concerns,” like an increase in youth use, a lack of traditional research, taking power out of the hands of pharmacists, a mandate to destroy patient records after 60 days and providing legal cover to doctors that make recommendations.

DJ Schanz speaks at a Utah Patients Coalition event.

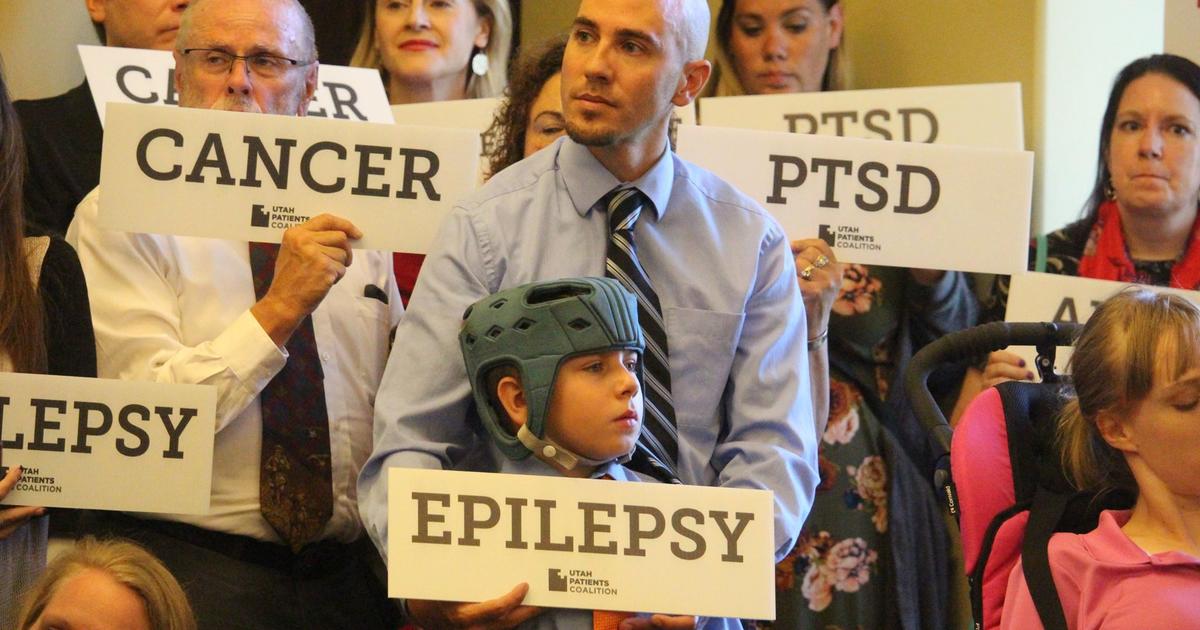

Even though Prop 2 has strong support among Utah voters, the Utah Patients Coalition (UPC), the group spearheading the legalization effort, has faced stiff opposition—and some would argue shady tactics—from Drug Safe Utah, the anti-legalization group that tried to keep medical marijuana off the ballot.

Comprised of the Utah Medical Association, the ultra-Conservative Eagle Forum, the Sutherland Institute and the Utah Chiefs of Police Association, Drug Safe is closely aligned with the all-male church leadership. Drug Safe has received $167,000 contributions (including $100,000 from a private citizen named Walter J. Plumb III and $20,000 from the Medical Association). UPC has raised $767,000 (including $261,000 from the Marijuana Policy Project and $50,000 from Dr. Bronner’s).

Update: On Oct. 4, UPC announced that it has made a compromise deal with Utah legislators, ostensibly taking the heat off of winning the measure. The legislation is similar to Prop 2, but doesn’t allow home growing, reduces the number of dispensaries and adds dosage requirements. However, Prop 2 will remain on the ballot. “While it’s difficult to walk away from a campaign after 18 months of hard work, this deal is undoubtedly a victory for Utah patients and their families,” Matthew Schweich, deputy director of the Marijuana Policy Project, which has bankrolled the effort, stated. “In Utah, a statutory ballot initiative can be amended or even repealed by a simple majority in the Legislature. If Prop 2 passed without any agreement on next steps, patients may have been left waiting years to access legal medical cannabis. This compromise eliminates that uncertainty and ensures legislative leaders are committed to making the law work… The compromise bill, while not ideal and cumbersome in certain respects, is workable and provides a path for Utah patients to legally access medical cannabis, including whole-plant products. This campaign was never about notching up another election victory. Our goal was simply to help medical cannabis patients in Utah who are being treated like criminals as they seek to alleviate their suffering. With this compromise, we have achieved that goal.”

Currently, Utah has a very restrictive, lawmaker-driven medical marijuana program in place. HB 195 allows those diagnosed with terminal illnesses access to medicinal cannabis and HB 105 (a.k.a. Charlee’s Law, named for Charlee Nelson, was enacted in 2014) permits CBD-only treatment for children with intractable epilepsy.

The Mormon church has not been shy about stating their views, especially around matters that intersect with perceived moral issues like drug use. For example, leadership counseled its members in 2008 to vote for California’s Prop 8 initiative that made gay marriage illegal and applied the same tactic with recreational cannabis initiatives in Nevada and California. When given as a directive, members tend to rally behind church guidance.

UTAH PATIENTS COALITION’S DJ SCHANZ: “The challenge in Utah, which may be somewhat unique to our state, is the influence that a single religious denomination can have on a huge swath of the population.”

Mormons are not necessarily opposed to cannabis, per se, but have strong opinions about how and why it should be used. Opinions about Prop 2 seems to boil down to the word “medical.” A Dan Jones & Associates poll from 2016 showed that support even then for medical marijuana hovered around 66%. But when asked about legalizing recreational marijuana, the results were flipped, with 77% opposed.

“The challenge in Utah, which may be somewhat unique to our state, is the influence that a single religious denomination can have on a huge swath of the population,” UPC’s treasurer DJ Schanz tells Freedom Leaf. “It’s a constant balancing act of winning over supporters in this demographic without being confrontational and abrasive to the organization, even with said religious organization’s subtle efforts to derail the ballot initiative.”

Utah Patients Coalition

Many stakeholders and policymakers in Utah believe marijuana can’t be a medicine if it’s smoked. Prop 2 does not allow for marijuana to be packages pre-rolls and specifies vaping only. Section 51 reads, in part:

«(6)(a) Except as provided in Subsection (6)(b), a cannabis dispensary may not sell medical cannabis in the form of a cigarette or a medical cannabis device that is intentionally designed or constructed to resemble a cigarette.

«(b) A cannabis dispensary may sell a medical cannabis device that warms cannabis material into a vapor without the use of a flame and that delivers cannabis to an individual’s respiratory system.»

H.B. 195 is also smoke-free.

Mormons are not necessarily opposed to cannabis, per se, but have strong opinions about how and why it should be used.

In the view of church leadership and many members, marijuana used in any way outside of a strictly-regulated, medicinal application turns it into a habit-forming and addictive narcotic. This leaves faithful members and ward leaders feeling torn about medical use, especially since the church has not provided clear guidance.

At a 2010 conference in Colorado Springs, priesthood leaders were asked what the official church policy was on medical cannabis. “It’s an issue between the church member, the member’s bishop and the Lord, to be made in consultation with the scriptures and Word of Wisdom,” was the general answer, the Salt Lake Tribune reported.

A Mormon bishop who wishes not to be named says he hasn’t had any members ask him for advice about using medical marijuana yet, but is certain it will eventually come up. “The counsel I would give them would have a lot to do with specific circumstances,” he confides. “I hope this is an evolving policy and that [church leaders] are open to further clarification in the future.”

Temple Square in Salt Lake City, UT

The church says they want more research, stating: “It’s in the public’s best interest, when new drugs undergo the scrutiny of medical scientists and official approval bodies.” Even Mormon Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) is pressing the federal government to lift the delays on cannabis research approvals.

But none of this may matter to Utah voters, about half of whom are active Mormons. A late August Dan Jones & Associates poll indicated that, despite the church’s vigorous disapproval, support for the initiative remains high, at about 64%, though down from 78% in July.

Unless the political winds shift, Prop 2 will most likely pass. Win or lose, when Utahans wake up on Nov. 7, they’ll still have a medical marijuana law on the books.

More Marijuana Initiatives on 2018 Ballot

Michigan Is Poised to Become the 10th State to Legalize It

Dueling Initiatives in Missouri Likely to Confuse Voters

Recreational Legalization on the North Dakota Ballot

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, subscribe to the magazine today!