Mexico’s President to the U.S.: We Don’t Want Your Armed Helicopters

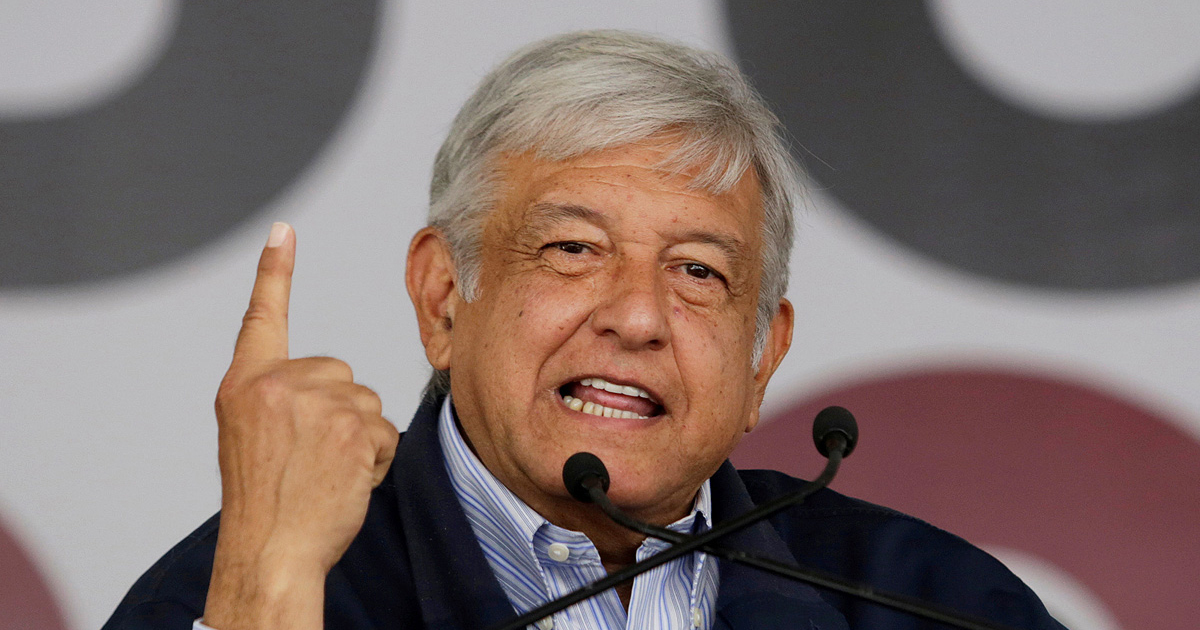

On May 7, Mexico’s new populist president, Andrés Manual Lopéz Obrador, announced his country was withdrawing from the Merida Initiative, the regional U.S.-led drug enforcement pact, and will be turning down the aid package offered through the program. “It hasn’t worked,” he told reporters in Mexico City. “We don’t want cooperation in the use of force, we want cooperation for development.”

He’s proposed across-the-board drug decriminalization in both nations and wants to “reorient” the program away from drug enforcement and toward social programs. “We don’t want armed helicopters or resources for other types of military support,” Lopéz Obrador, who’s known as AMLO, declared.

ALMO: “We don’t want cooperation in the use of force, we want cooperation for development.”

Since 2007, the U.S. has supplied the Mexican military and police with training and equipment under the $1.6 billion Mérida Initiative, which also includes the Central American nations. Most of the big transfers of military equipment were made early in the program, and in recent years more of the funding has gone toward training police and prosecutors in an effort to reform Mexico’s notoriously corrupt justice system.

Economic development in Mexico’s Southeastern states and Central America could help stem the tide of migration, ALMO contends. These plans were actually officially endorsed by Washington in a “Mexico-United States Declaration of Principles on Economic Development and Cooperation in Southern Mexico and Central America” that both governments signed after he took office in December, although the U.S. didn’t actually pledge any new funds for that program.

Bilateral Decrim Proposed

Along with his announcement, AMLO’s office released a 2019-2024 National Development Plan that contained the radical notion of jointly negotiating a general drug decriminalization with the United States. “The ‘War on Drugs’ has escalated the public health problem posed by currently banned substances to a public safety crisis,” the document reads, adding that the current “prohibitionist strategy is unsustainable.”

The development plan explicitly states that abandoning this strategy is “the only real possibility” to address continued drug cartel violence: “This should be pursued in a negotiated manner, both in the bilateral relationship with the United States and in the multilateral sphere, within the UN.”

Marijuana Policy Project executive director Steve Hawkins hailed AMLO’s proposal, saying it “reflects a shift in thinking on drug policy that is taking place around the world, including in the UN.”

While getting the Trump administration to go along with the idea challenges the imagination, AMLO’s proposal certainly shifts the debate in the right direction.

Cannabis Legalization Pledged in Mexico

Mexican lawmakers are already taking a first step toward this agenda by pushing for cannabis legalization. Legislation is being hashed out over the summer recess, which runs from May 1 to August 31.

A preliminary version of the bill permits cultivation of up to 20 plants for personal use on private property and under a regulatory regime.

Mexico’s Senate Health Committee held hearings this year on cannabis legalization, which was mandated by a ruling of their Supreme Court last October. That decision found cannabis prohibition unconstitutional on individual liberty grounds and imposed a 90-day deadline for the country’s Congress to bring the law into conformity with the ruling. That deadline has since expired and was extended to October.

Drug-War Violence Continues – For Now

AMLO ran last year on a promise to de-escalate the country’s relentless narco-violence, with the slogan of Abrazos, no balazos (Hugs, not shoot-outs). Upon taking office, he declared the drug war was over. But AMLO’s new approach has yet to result in significant changes – at least, not yet. The number of homicides in Mexico hit a record 8,493 in the first quarter of 2019. An estimated 200,000 people have been killed in Mexico since President Felipe Calderón first mobilized the army to fight the cartels 13 years ago.

Last year, the country’s murder rate climbed to 33,341, a 33% increase over 2017. That’s nearly twice as many homicides committed in the U.S. annually in a country with one-third the U.S.’ population.

Despite AMLO’s declaration of drug peace, military troops are still being mobilized against traffickers and campesino cannabis growers. AMLO’s big development plans for the impoverished south have been adamantly opposed by the Zapatista rebels and other peasant and indigenous organizations of the region who fear the loss of their lands to tourism and mega-projects.

RELATED

Vicente Fox’s Global Vision: Legalization of All Drugs

A Brief History of Marihuana in Mexico

Where Not to Go in Mexico: The 16 Most Dangerous States

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, subscribe to the magazine here