Getting High on Oversupply: What to Do About Surpluses and Shortages

The rollout of marijuana legalization has not been smooth. On one side, there’s a push for revenue; on the other, there’s a desire for tough regulations and enforcement. While businesses get caught in the middle, consumers go along for the ride and patients run the risk of being mowed over.

Greed Rules: The Case of Oregon

Legislators often see legal marijuana as a cash cow. If money is the motivation, authorities will push to issue as many licenses to as many businesses as possible, which can lead to overproduction and oversupply. Take the legal marijuana state of Oregon, for instance.

People in Oregon grow a lot of weed. The Beaver State has been a net marijuana exporter for decades. The state’s medical-marijuana program was approved by voter initiative in 1998, yet it wasn’t until 2013 that the state legislature passed a bill to license and regulate dispensaries. Voters approved a legalization measure in 2014 and adult-use sales started in 2015. Then, in 2016, the legislature repealed a residency requirement for marijuana businesses and opened up Oregon’s marijuana industry to out-of-state investment.

“We’ve created an oversupply problem,” says Anthony Taylor, co-founder and legislative liaison for the patient advocacy organization Compassionate Oregon. “Before we legalized cannabis for the adult-use population, we were already producing about five times what the state consumes, and when the Oregon Liquor Control Commission came in and threw all that infrastructure away in favor of their new infrastructure, it created this situation that’s virtually collapsing in on itself.”

Legislators often see legal marijuana as a cash cow. If money is the motivation, authorities will push to issue as many licenses to as many businesses as possible.

Taylor’s not just blowing smoke about over-production. According to an August 2018 report by the Oregon-Idaho High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area program, “A surplus of 344,730 kg (760,000 pounds) unsold cannabis [was] logged during the recent audit of the recreational system.” Clearly, Oregon is growing more cannabis than can be consumed in the state, hence the proposal by State Sen. Floyd Prozanski to be able to ship the surplus to neighboring legal states.

On the bright side, not everyone is suffering. Oversupply, combined with intense competition, pushes retail prices down (as low as $40 per ounce), and non-medical consumers reap the benefits. Retailers benefit as well because oversupply gives them leverage to negotiate lower wholesale prices.

Gripping Too Tightly: A Look at Canada

Plants hanging to dry. (Photo by Ed Rosenthal)

While an over-abundance of cannabis is a huge problem for growers, at least in the short term some people are happy. With undersupply, no one’s happy. That’s the problem Canada has been facing since legal adult-use sales began last October 17.

Canada’s had legal medical marijuana since 2001, following a Supreme Court ruling in 2000, and a largely unregulated medical industry developed as a result. The Canadian government finally passed the Marijuana for Medical Purposes Regulations in 2013, which required patients to get their weed from licensed producers via mail order. (That requirement was overturned by the Canadian Supreme Court in 2016.)

In 2015, when Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party took a majority in the federal elections, he became prime minister. Trudeau had promised to “design a new system of strict marijuana sales and distribution,” but the program so far has been struggling.

With undersupply, no one’s happy. That’s the problem Canada has been facing since legal adult-use sales began last October 17.

“Stores have had to cut hours,” Vancouver-based researcher, writer and marijuana activist Chris Bennett tells Freedom Leaf. “They don’t have stock for meeting demands and it’s expected to be a year or more before this situation levels.”

Scarcity means higher prices. Weed in Canada costs “about $16 a gram for legal pot compared to the typical $8-$12 that you could find at most dispensaries,” he says. “Plus, there’s been numerous quality issues with the ‘legal’ cannabis being sold.”

It didn’t have to be this way. “The current legalization is largely seen by activists, dispensary owners and growers as an industry takeover,” Bennett adds. “If the Fed and Provinces had taken a more inclusive approach, existing dispensaries and growers could’ve been grandfathered in.” And, hence, prevented the shortages that are currently plaguing the program.

The Road Ahead

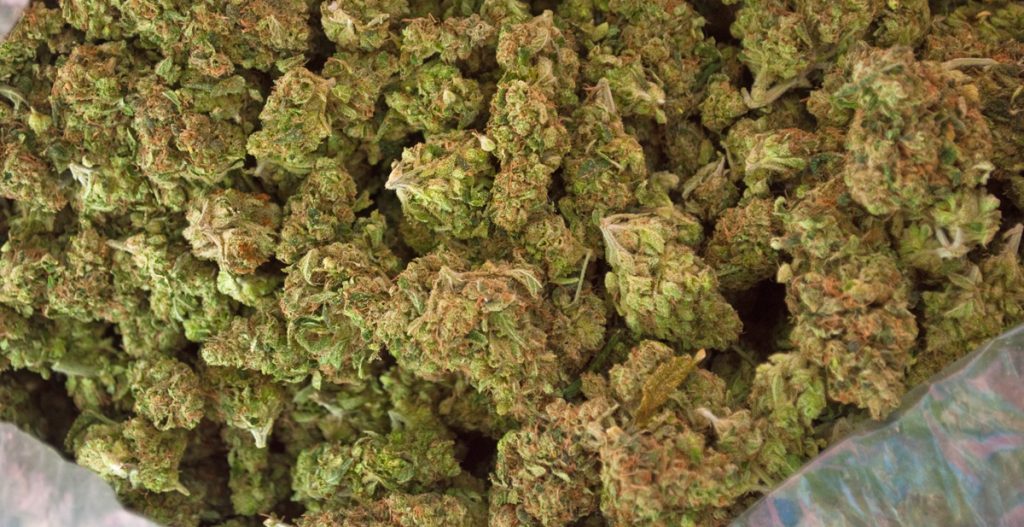

Buds nicely dried and cured

Here’s Anthony Taylor’s advice for states and countries that plan to create regulated cannabis markets in the near future:

- “Don’t regulate it like alcohol. They’re two different creatures and they need two different sets of regulations.”

- “Create an independent, autonomous body to oversee all things cannabis, with the requisite rule-making authority, and allow the process to take several years, especially if you have an existing medical infrastructure in place.”

As far as Oregon’s oversupply problem is concerned, he suggests licensing “a very small population of growers and see what happens. Don’t open it up for anybody in the world to come in and buy an Oregon Liquor Control cannabis license. Use a progressive licensing structure so that the mom and pops only have to pay $1,000 for a license, but the Coors, Marlboros and RJ Reynolds come in and pay $5 million. That’s a very important distinction to make, because it allows the small farmer to continue to grow and become an important part of the overall picture.”

Related Articles

Pounds Selling for $500 in Oregon

Inside Canada’s Legalization Challenge

Social Consumption Taking Off in California and Colorado

This article appears in Issue 35. Subscribe to the magazine here.