George H. W. Bush: The Last American Drug Warrior President

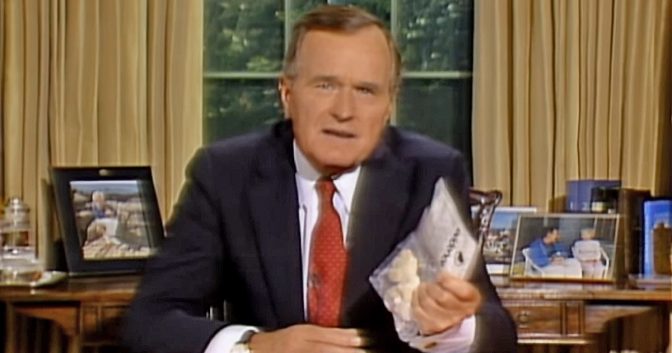

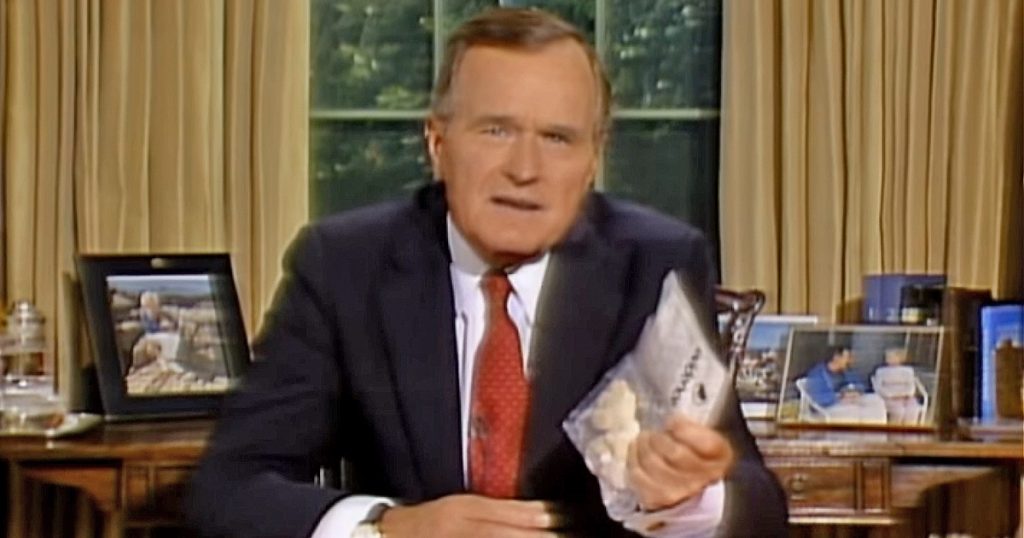

Infamously, President Bush convened a live TV press conference in September 1989 where he held up for the cameras a small bag of crack cocaine.

By every measure, America’s 41st president George Herbert Walker Bush, who passed away Nov. 30, was a fine man, father, patriot, civil servant and elected policy maker, decent and moderate, certainly by today’s standards.

However, likely due more to his age than social disposition, President Bush was the last great standard bearer of American presidents who publicly proclaimed the absurd idea that a “War on Drugs will be won.” After Bush Sr., such fanciful notions were never heard again from Baby Boomer presidents Bill Clinton, G. W. Bush, Barack Obama or Donald Trump, and are no longer part of the American political lexicon.

As a former head of the Central Intelligence Agency and Ronald Reagan’s Vice President (from 1981-1988), President Bush was a committed drug warrior in the worst way, overseeing during his tenure as president the implementation of Reagan’s Just Say No drug war by dutifully rolling out mass drug testing, controversial civil forfeiture enforcement, enhanced policing and the ensuing swelling of prosecutions and incarcerations.

The Bush administration was responsible for the creation of the bloated and ineffective Office of National Drug Control Policy (a.k.a. the Drug Czar’s office), appointing as its first two directors the bombastic William Bennett (a.k.a. the Drug Bizarre) and former Florida Republican Gov. Richard Martinez. The Drug Czar’s office was (and still is) responsible for quarterbacking anti-marijuana propaganda, such as the DARE program in public schools, Partnership for Drug Free America campaigns and anti-drug non-profit organization funding.

As a former head of the CIA and Ronald Reagan’s Vice President from 1981-1988, President Bush was a committed drug warrior in the worst way.

Infamously, President Bush convened a live TV press conference in September 1989 where he held up for the cameras a small bag of crack cocaine, claiming that “drugs are so easily obtained in America that crack could be readily purchased at the park across from the White House.” However, the reality was that DEA agents lured a teenager away from their distant neighborhood specifically to set him up at Lafayette Square, the park directly across from the White House, purely for propaganda reasons (the 19-year-old user ultimately received a 10-year prison sentence for selling crack).

A frequent target of the federal government under Bush was High Times magazine, which, pre-Internet, was one of the only publishing outlets that focused on marijuana. In 1990, the DEA’s Operation Green Merchant accused High Times of being a conspirator to distribute Dutch cannabis seeds in the U.S. via advertisements. The case against High Times was ultimately dropped, but not before gutting the magazine of numerous cultivation advertisers, many whom were shut down and arrested. Another magazine, Sinsemilla Tips, did not survive Green Merchant.

Despite public and local political support at the state and local levels, Bush fought against any medical access for cannabis products for qualified patients with a doctor’s recommendation, most notably appealing the DEA’s slam dunk loss legally in the seminal court proceedings making the case for cannabis’ rescheduling, NORML vs. DEA, where the agency’s own chief administrative law judge, Francis Young, ruled conclusively that cannabis is a safe, effective and non-toxic herbal drug (“marijuana in its natural form is one of the safest therapeutically active substances known to man,” he wrote) and should be rescheduled in the Controlled Substances Act immediately. Jack Lawn, the DEA administrator who chose to ignore Young’s ruling, eventually become CEO of the Distilled Spirits Council, the alcohol lobby group in Washington, DC.

Instead of accepting defeat (and science), the Bush administration appealed Young’s ruling to the ultra-conservative DC Court of Appeals. In 1994, with Bush long out of office, marijuana law reformers lost the appeal in a 2-1 decision.

H. W. Bush’s Drug War Ultimately Led to Marijuana Law Reforms

Remarkably, while the War on Drugs reached new heights under Bush, a counterculture effort surrounding public interest in cannabis and the need for medical patients to have legal access—fueled by anger at the aggressive enforcement of cannabis prohibition laws as well as the scientific denial of marijuana’s safety and efficacy as a therapeutic drug—started to take shape when, in 1991, San Francisco voters passed Prop P, legalizing medical use in the city.

During Bush’s White House run from 1989-1992 (he lost his reelection bid to Bill Clinton in 1992), more than a dozen Democrat and Republican presidential wannabes—almost all Baby Boomers who’d partied during the ’60s and ’70s—admitted to having “experimented” with marijuana in their teen years and while in college. Bush’s son, George W., who would be elected president in the contested 2000 race, was among them (he’s used coke and pot). To wit: While Supreme Court Justice nominee and Harvard Law professor Douglas Ginsberg’s cannabis-use admission forced him to withdraw in 1987 (he was nominated by Reagan), Bush’s own Supreme Court nominee, Clarence Thomas’ similar revelation failed to derail his nomination two years later.

Due in part to the excesses of drug warring under Presidents Reagan and Bush, highly agitated and motivated marijuana law reformers thankfully started a slow but sure climb from the depths of cannabis prohibition.

By the end of the first Bush presidency, the “Internet,” a new and generation-changing form of communication and social organizing, was emerging. In the coming years, cannabis law reform organizations would maximize the use of this new communications and information medium to largely level the playing field against the government spending billions annually to enforce cannabis laws and oppose most marijuana law reforms. Email, electronic bulletin boards, chat rooms, webpages and RSS feeds—all immensely affordable to the average family—empowered non-profit drug reform organizations to ultimately counter government anti-marijuana misinformation and propaganda in ways that were not previously possible.

Importantly, this period gave rise to a core group of marijuana law reform organizations and individuals, such as NORML, Drug Policy Foundation, Marijuana Policy Project, Cannabis Action Network and High Times and extraordinary activists like Jack Herer, Dennis Peron and Brownie Mary. Consequently, due in part to the excesses of drug warring under Presidents Reagan and Bush, from this juncture forward in American history, highly agitated and motivated marijuana law reformers thankfully started a slow but sure climb from the depths of cannabis prohibition in the late ’80s to recreational legalization in several states by 2012.

Related Articles

Barack Obama: A Presidential Reefer Retrospective

«Just Say No» Nancy Reagan: Death of a Drug Warrior

Richard Nixon on the Drug War, Blacks, Hippies, Gays and Jews

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, subscribe to the magazine here