Excerpt from Ed Rosenthal’s ‘Beyond Buds’: The Rosin Revolution

Rosin is a concentrated blend of terpenes and cannabinoids extracted using a method sometimes called “rosin tech” (RT). It’s the simplest, least-expensive way to extract concentrate from raw buds or hash for more effective dabbing.

Instead of a chemical process, rosin tech relies on heat and pressure to squeeze cannabinoids and terpenes from the source material. It’s a very fast process: A batch of rosin can be produced in moments and consumed immediately. Another advantage of rosin production is that it poses minimal risk of physical injury.

Rosin is the simplest, least-expensive way to extract concentrate from raw buds or hash for more effective dabbing.

The physical science of rosin is simple: Applying heat melts the terpenes and cannabinoids into a pliable resin. Then it’s squeezed using a press. Some lipids and waxes melt at the same temperatures. Thus, the finished product is generally not as refined as the results of some other methods. The tradeoff is the speed and ease of extraction.

There’s a wide range of tools and equipment that can be used to make rosin. The choice depends mostly on the quantity being pressed. On the hobby level, you can use household items. Industrial processors use pneumatic or hydraulic presses.

No matter the size of the project, the start-up costs of this method are very low compared to chemical extraction, where just the cost of the safety equipment and laboratory modifications exceeds the cost of even an elaborate, large-scale rosin operation.

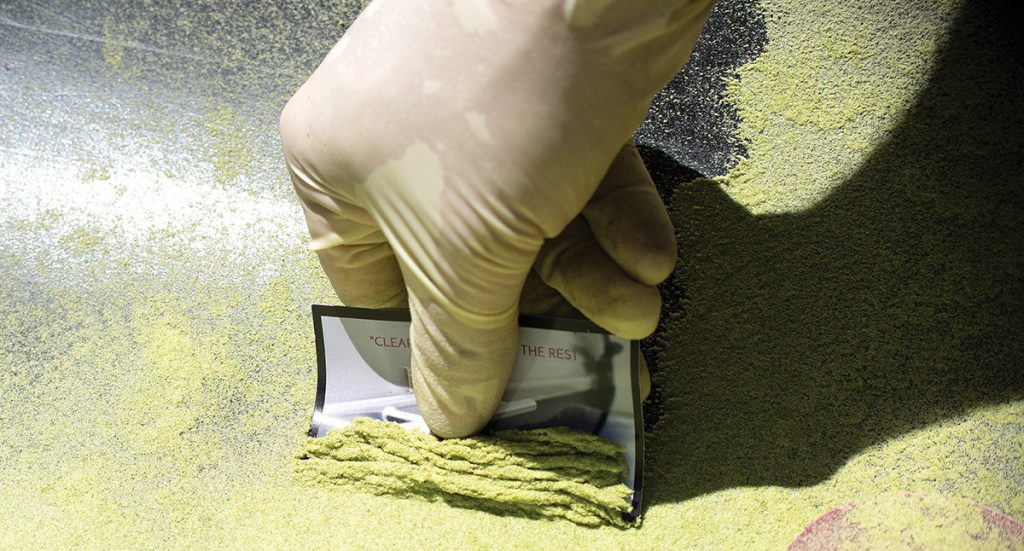

Kief can be used to make rosin

Starting Material

There are three basic types of material you can press rosin from: buds, hash and kief. Within those categories there are different types and grades.

Buds

Freshly cured, resin-rich flower (small buds and trim are ideal) results in the best rosin, because it’s rich in terpenes and high in cannabinoids. Conversely, older, drier material results in lower yields that are darker, less flavorful and less potent.

An ounce of buds yields about five grams of rosin.

Kief

Dry-sift kief generally contains a high percentage of plant material. The more plant matter removed from the trichome heads, the higher the yields and the cleaner and smoother the resulting rosin.

Hash

When rosin is pressed from hash, it’s a secondary concentration, a refinement of an already concentrated product. This results in a higher concentration of cannabinoids in the rosin.

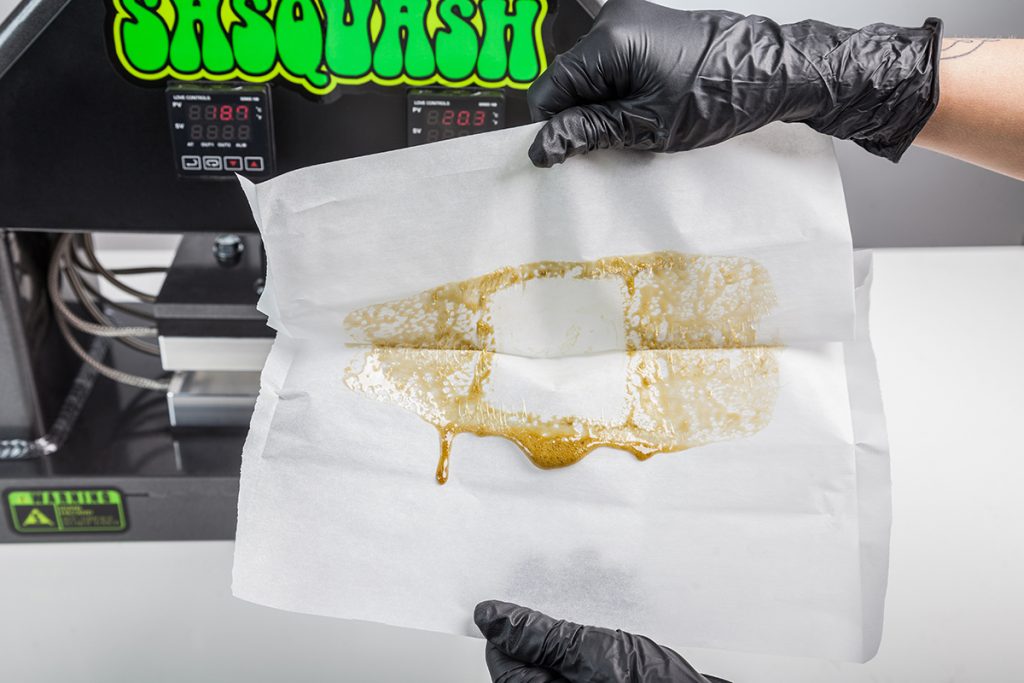

Sasquash rosin press

Machine Pressing Rosin

Rosin processing, though not a cold process, occurs below the volatilization point for most of the terpenes and doesn’t reach the temperatures needed for decarboxylation. The rosin is mostly a concentration of THCA and/or CBDA, the acidic precursors to the cannabinoids. The result: the material is great for smoking, but will not be intoxicating if eaten.

Choosing a Press

One option for those new to concentrate production is to choose an entry-level, mid-sized, tabletop model press like those made by Sasquash that offer higher-volume capacity than a hair straightener without the investment and storage concerns of a large press.

If you do choose to purchase a press, a big factor is the amount of pressure it produces. You don’t need to buy a press that produces 25 tons of pressure when all you need is two to five tons to press small quantities of hash or bud. Pressing several ounces of bud or hash at one time requires 10 to 25 metric tons of pressure.

Most commercially available, rosin-specific presses are designed to press hash only. If you’re planning to press flower, choose a machine that is designed to handle it. They require more pressure than hash-pressing models.

Tools for Making Rosin

Pre-Press Molds

In addition to the press, there are a number of other items to consider. Pre-press molds are a crucial component of many smaller rosin presses, so it’s important to pay attention to the specs. Pressure affects yield. To maximize pressure, use the same force in the smallest area possible.

Rosin filter bag

Filter Bags

It’s possible to do a “naked press” on a bud—pressing it without any physical screen or filtration to remove plant material. But if you want to further refine your product and confine your material to a condensed area (without the trichome loss incurred using molds or hand pressing), filter bags are an excellent option and should be used for large quantities. They’re available in several micron sizes like bubble bags used in cold-water extraction.

Parchment Paper or PTFE Sheeting

No matter what approach to RT you choose, parchment paper is absolutely essential. That’s parchment paper—NOT WAX PAPER. Make sure the paper you choose doesn’t have any coating.

Making rosin is a sticky endeavor.

Machine Pressing Flower

Pressing buds yields between 10% and 35% of the original material, roughly corresponding to the cannabinoid content of the starting material. If a strain tests around 20%, expect a yield of about 20% of the material’s weight in rosin under optimal conditions. An ounce of buds yields about five grams of rosin.

Before pressing, make sure the relative humidity of the material is just right: too low and your yield and quality will suffer, too high and your rosin will be difficult to collect or will smell and taste like chlorophyll and may even turn green. Generally speaking, you’ll want to use material with a relative humidity level of 55% to 60% You can measure this using a hygrometer, either a basic analog model like what’s found inside a cigar humidor, or purchasing a digital hygrometer for $10 to $15. If your bud is too dry, use a humidity pack like those sold by Boveda specifically for cannabis.

Always cut and fold parchment paper before pressing. Filling or ripping parchment in the middle of a job is messy, awkward and inefficient.

Lowering temperature usually results in higher quality, but this is not always the case, and lower temperatures will reduce yield, sometimes drastically; it depends on the starting material quality and “personality”—the collective idiosyncrasies and physical quirks that affect how it reacts to pressing. A good way to judge how long to keep the bud under pressure is to watch the color of the oil and how it’s flowing. Once the flow starts to darken and slow down, it’s time to remove pressure.

Some producers choose to start high and work their way down, but we recommend starting at a low temp and working up until you notice a deterioration in quality. Your goal is an even balance between yield and quality. You should be able to roughly dial in your ideal temperature for a given strain within four or five test runs. If you want to refine your temperature to the precise “Goldilocks Zone” for pressing, you might need eight to 10 test runs. But once you have a batch dialed in, you’ll be able to use the setting, or combination of settings, for the rest of that run.

A good way to judge how long to keep the bud under pressure is to watch the color of the oil and how it’s flowing. Once the flow starts to darken and slow down, it’s time to remove pressure.

Most rosin extractors heat the material 150º F to 250º F range. This varies based on the material’s relative humidity, which also affects yield. Always check yields and rosin quality at different temperatures to determine the best setting for a particular batch.

Make sure to be consistent with the amount being pressed. Spread the bud so it forms an even layer. Don’t over-process your buds before pressing. Many processors feel like they get a better press from mostly intact buds versus broken or ground material, but others just break everything down to the same size and make an even layer.

Once stems are removed and flower is weighed to the desired amount, place two small buds in the filter bag first and make sure they’re packed into the corners tightly. This prevents loss of oil to the corners. Once they’re packed, fill the bag with the remaining material evenly with no voids and an even thickness of between a quarter inch to a half inch, leaving a one-inch flap for a fold. There will be two additional corners after the fold; fill these voids to ensure even flow and prevent loss.

Once the trichomes have melted, apply full pressure. You should start to see oil flowing from the platens. Depending on how fast the extraction is happening and the amount being pressed, keep pressure on the material for 35 to 90 seconds. The reason for the time variation is that flow rates vary by variety and freshness. Slow-flow flowers require pressure and heat for a longer time period. Fresh flowers with fast-flowing oil should be pulled off the heat quicker.

Oil oozes onto the parchment paper.

Collecting Rosin

Gathering up rosin after pressing is often more challenging than the press itself. Depending on starting material, its moisture, temperature and timing, a wide range of consistencies can happen. It can be a stable, easy-to-gather material or a sticky sap. Hash rosin is more stable (less sticky and gooey) than flower rosin, which is often difficult to gather.

No matter what consistency you’re working with, it’s probably best to work in as cold a room as possible, ideally with cold work surfaces, to increase or maintain the rosin’s manageability while you collect and package it. Make sure you wear gloves to prevent contamination with skin oils and to avoid getting rosin stuck to your hands.

After pressing out the rosin, leave all the papers in the refrigerator for about five minutes to cool everything down and stabilize the oil. Cold plates or cold blocks can be used to help with collection; an aluminum plate left in the refrigerator or sitting on a block of ice is an ideal cold surface.

Avoid scraping parchment paper; this can result in paper particles being scraped into the final product.

Freshly-made rosin using the Sasquash press

Curing and Storage

After collecting the rosin and rolling it into a ball, there are several ways to cure it. A large ball is a good way to protect most of it from oxidization and to prevent the evaporation of terpenes.

Always store rosin in a sealed container in the refrigerator. This preserves terpenes and prevents oxidization. If you don’t plan to weigh it out, leave it in a large ball inside of a sealed container.

The final rosin product

Low-Temp Dabs

Now that you have your resin, we recommend low-temperature dabbing. While hot dabs are how most dabbers were introduced to dabbing, thankfully this is no longer necessary, now that low-temp dabbing has become the majority practice. The key to effective dabbing is finding the ideal balance between preserving the terpenes while activating the cannabinoids. The problem is that the vitalization point of most terpenes is far below the boiling point of most cannabinoids. Compromises must be made.

Lower temps mean higher terps and less activated cannabinoids; higher temps mean lower terps and higher cannabinoid activation. Low-temp dabs utilize low pressure achieved through restricted airflow via a carb cap. Carb caps restrict and direct airflow, lowering the pressure and by extension the boiling points of both the terpenes and cannabinoids present. This allows for a flavorful, low-temp dab that still contains higher levels of active cannabinoids.

Excerpted from Beyond Buds: Next Generation. © 2018 Ed Rosenthal. Reprinted by permission of Quick American Publishing, Piedmont, CA. Written with Greg Zelman.

Related Articles

This article appears in Issue 34. Subscribe to the magazine here.