Exclusive Book Excerpt: When Cheech Met Chong

Vancouver is one of the most beautiful cities in North America, and in 1969 it was the “San Francisco of Canada,” with all the counterculture implications—only Canadian, so it was more polite… as in “Can we please have a revolution?”

On my first day in Vancouver, my roommate Len MacMillan took me to the corner of Main and Pender, the most squalid point in the city. It was the conjunction of Chinatown, Skid Row and Junkyville.

As we walked by a nightclub named the Shanghai Junk, I couldn’t help but notice their promotional photos in a little waterlogged glass showcase. “The Junk,” as I was to come to know it, was Vancouver’s first topless bar. Light-years from what we know as a topless bar today, these ladies wore large pasties with tassels and sequined underwear.

The photographs in the case showed the ladies interacting with some fully clothed hippie/greaser guys dressed in police uniforms with army helmets on.

My first reaction was, “What the fuck is this?”

Oddly enough, I’d seen something similar when I was in high school. There was this place on Ventura Boulevard in the Valley called the Zomba Cafe, and it was a burlesque house that featured strippers and comedians. But I just thought these photos were odd and funny and walked on.

About a month later, I ran into a high school buddy of mine from Los Angeles who was in Vancouver because of his difficulties with the draft. Hank Zevallos was an odd character. He was senior class president. He also ran track and was an aspiring writer who wrote for the school newspaper.

Hank told me that he and another guy, a Ukrainian named Ihor Todoruck, had started a music-scene magazine called Poppin. They had ambitions to be bigger than Rolling Stone, but right now they were selling their publication on the streets of Vancouver. Hank, who was the editor, remembered that I used to do some writing for the school newspaper and suggested that I could write some pieces for Poppin.

Whatever.

Whatever.

“I could put your name on our masthead,” Hank continued. “You could get free albums and get into shows free and get free drinks and food.”

Now I was listening.

In short order, I went to a bar and was introduced to Ihor, the magazine’s publisher. After a long conversation and a few short drinks, in which I briefed him on my background, Ihor said I could work with Hank and write for them.

Before I left the bar, Ihor gave me a mischievous smile and said, “There’s this guy I think you should meet.”

He said he knew this guy named Tommy Chong who was running an improvisational theater company in a top-less bar in Chinatown. I quickly realized that he was talking about the Shanghai Junk, the bar I had passed when I was walking around with Len that first day.

Eventually, I’d realize that Tommy was the musician that everybody in Calgary knew because he had co-written the song “Does Your Mama Know About Me?” that Diana Ross and the Supremes had recorded. It was first a hit for Tommy’s band, Bobby Taylor and the Vancouvers, on Motown Records. He was a legend in Calgary. The song went on to be recorded by other performers, too, like Stephanie Mills, Jermaine Jackson and the Harlettes, Bette Midler’s backup singers.

As we came off the stage, one of the band members asked, “Well, when’s our next gig?” Tommy and I both looked at each other and knew the answer. There would be no next gig for the band. We were now a bona fide comedy duo.

Ihor set up a meeting, and we were to meet at a farmhouse out in the countryside. On the appointed day, I drove out there and knocked on the door, which was quickly opened by a very pretty young blonde hippie-type chick. It was Shelby Fiddis, Tommy’s girlfriend, a person I would come to know very well for the next forty years (and counting). Crawling around the floor was an angelic little one-year-old girl with cookie smeared all over her face, Precious Chong. Tommy came out from a back bedroom, and at the instant we first laid eyes on each other, we both had the same thought: “What the hell are you?”

Tommy was wearing brown leather pants held up by a wide leather belt fastened to a handmade hippie belt buckle. He was also sporting a blue nylon wifebeater T-shirt that revealed a crude, homemade eagle tattoo on his left arm where one wing was bigger than the other… and not on purpose. He had long, wild black hair parted in the middle. To top it off, he had a scraggly and sparse Fu Manchu moustache and goatee… and he was brown, which I took to be a good sign.

The overall effect was of a hippie-biker Mongolian weight lifter. And he had gold-framed eyeglasses and a big gap in his front teeth. You know, your typical topless-bar improvisational-theater look.

I was sporting the exact opposite look. Working at Sunshine Village Ski Resort required a short haircut and no facial hair. I looked like a narc, which everyone in the troupe would suspect at first.

I began filling Tommy in on my background, starting with my draft-resister status and ending with my experience as a member of Instant Theater, an improvisational theater group in L.A. A total fucking lie, but a very good improv. I had seen Instant Theater many times and immediately knew I could do improv.

Tommy knew that I was a writer for Poppin magazine, so he hired me as a writer for the group. But first I had to come down and check out the show to see if we were a fit. I asked him how much the job paid, and he said sixty Canadian dollars a week.

Right away, I knew we were a fit.

Do You Have a Nickname?

Very quickly we heard of this “battle of the bands” at the Garden Auditorium. Perfect place to try out our new act. We got a time slot for Tommy Chong and the City Works. I had heard Tommy say more than a few times that the next act or group he was in would have his name in the title. He didn’t want to be anonymous like he was in Bobby Taylor and the Vancouvers. I totally understood. I wanted exactly the same thing.

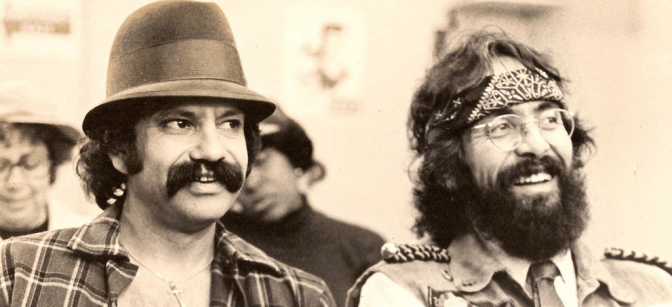

Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong at New York’s Bitter End in 1972. (Photo by Allen Green

We decided to begin with a couple of comedy bits and then play some music. We started out with “Old Man in the Park,” where Tommy plays a crotchety old geezer and I play a biker. We have a conversation, which is pictured on the back of our first record album. We began performing the bit while everybody was still milling around. Very quickly a bunch of people rushed to the front of the stage. I thought they were going to jump onstage, which is what we were used to, but they just wanted to hear what was going on. These kids, for the most part, would never have gone down to the Junk. So while they never heard of us… we were them. When we finished the bit, we got a big cheer. We knew what a rock‘n’roll audience was like. We both had been musicians and performers all our lives. I’d been in a number of bands all through high school and college. Tommy, the same. We had more to give them, and we did.

We went into another bit, and most of the arena had quieted down and were following us. They wanted another bit and then another. We never got around to the music. The band stood there the whole time. We got a rousing rock‘n’roll reception. As we came off the stage, one of the band members asked, “Well, when’s our next gig?” Tommy and I both looked at each other and knew the answer. There would be no next gig for the band. We were now a bona fide comedy duo.

As we drove home in Pop Chong’s car, we were floating on a cloud of euphoria. In Vancouver, where it always rains, it’s necessary to have windshield wipers that work. Ours did, but the windshield-wiper motor had been broken for a while. The wiper was hooked up to a straightened-out wire clothes hanger that the driver used to move the blades back and forth… by hand. We didn’t care, though, as we drove along bursting with joy. We went back and forth going over the show and how the audience responded. We were thrilled that they not only listened and laughed, but that they didn’t throw shit at us.

Soon we were driving along in a happy silence. While working the windshield wiper, Tommy seemed lost in a reverie.

“We need a new name.”

We both realized that “Tommy Chong and the City Works” would not work if there were just the two of us. So we tried out all the combinations.

Marin and Chong.

Chong and Marin.

No. Both sounded too much like an ambulance-chasing, “Se habla Español… and Chinese” law firm.

Tommy and Richard.

Richard and Tommy.

No. Sounded like two white guys.

Then finally, Chong asked, “Do you have a nickname?”

“Well, my family calls me Cheech, which is short for chicharrón.”

“What’s a chicharrón?”

“It’s a pork rind, you know, a deep-fried pig skin. They’re all curled up and small. When my uncle Bano saw me for the first time in my crib he said, ‘He looks like a little chicharrón.’ It very quickly got shortened to ‘Cheech,’ and that was always my nickname in the family. Everybody in my family had nicknames, usually two or three.”

Chong said softly, “Cheech, Cheech.” And then “Cheech and Chong.” And that was it.

We didn’t even try “Chong and Cheech.” We were both musicians, and our ears told us that name had the right sound. Cheech and Chong… and that’s the way it’s always been. We drove into the rain, over a bridge that was condemned and had a big sign that warned PROCEED AT YOUR OWN RISK.

Tommy, while still working the wiper by hand as we disappeared into the fog, softly chanted, “Cheech and Chong, Cheech and Chong… Man, we’re gonna be big.”

One Small Problem

Though we didn’t know it at the time, and hadn’t planned it, our first gig as Cheech and Chong was at that battle of the bands at the Garden Auditorium. We played one more gig in Vancouver atRonnie Scott’s Blues and Folk Club on Davie Street. It was May 1970.

Scott’s was the epicenter of the blues and folk scene in Vancouver. We were opening for blues great T-Bone Walker. Once again, people in this scene had never seen us, but we went over great.

T-Bone was very late getting on, and when he did show up, he was totally drunk and had to be helped onto the stage. He sat down in his chair, and a roadie laid a guitar in his lap. The band,which had already started to play, waited for him to join in.

Finally, he started playing his guitar and singing in a very drunk voice, slurring all his words. The strings on his guitar had been loosened for the plane ride, so they were all out of tune. But it didn’t bother T-Bone, because he just kept singing and playing. I don’t think he even knew where he was. A roadie crept onstage and tried to tune as he played, which only seemed to annoy him. The band finished the tune, and the audience leapt to their feet to give him a standing ovation.

Tommy and I almost fell over laughing in the back of the room.

Later on, Chong would use that performance as the basis of his blind blues singer Blind Melon Chitlin, which is still in our act today.

After the show, Chong and I had a conversation about what we would do next. If we really wanted to make it, we would have to go to either Los Angeles or New York. New York was cold and we knew nobody there, Los Angeles was warm and I grew up there. There was only one problem: I was wanted by the FBI because of my draft-resistance activities.

Chong said softly, “Cheech, Cheech.” And then “Cheech and Chong.” And that was it.

You must remember that there was total bureaucratic and administrative chaos in the United States at this time. The Vietnam War was raging, and a huge portion of the country, especially college-age kids, were doing everything they could to fuck with the government. I figured they were never going to notice li’l old me. This was well before the computer age. They were still making carbon copies of shit.

So I went to the airport armed with a phony ID. It was the driver’s license of my friend Bill Knorr… with his picture on it.

Still, I was a little bit nervous… so, I looked for a bar at the airport. I saw something Irish sounding with a shamrock on it so I went in and ordered a double vodka on the rocks.

My cover story, if I needed one, was that I was a writer for Poppin magazine, which I was, and I was going down to the U.S. to do some interviews with the Grateful Dead, Santana and the Jefferson Airplane. I ordered another shot. I downed it as soon as it came and then got up and walked to Gate 34.

Rounding a corner into a long hallway of gates, I saw Led Zeppelin coming out of a door at the other end. Robert Plant and Jimmy Page led a gang of roadies. There was nobody else in the hallway. They acted like they were being attacked by a hundred groupies. They were laughing at the top of their lungs as they pretended to kick them away and fight their way through the nonexistent crowd. I thought I was in the movie Blow-Up.

I steeled myself for my interaction with the U.S. border officer. As I showed him my phony ID, I leaned in closely so that he could get a whiff of the vodka on my breath. I wanted to make sure he believed that I was a journalist. I started telling him my story of going to get interviews. He stopped me in the middle of the story, handed me back my ID with Bill Knorr’s picture on it and said, “Welcome to the U.S.”

I stepped across the line and, after three years, I was back home.

Excerpted from Cheech Is Not My Real Name… But Don’t Call Me Chong. Copyright © 2017 by Cheech Marin, Reprinted by permission of Grand Central Publishing, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, subscribe to the magazine today!

Related Articles

13 Questions with Tommy Chong on His 80th Birthday

80 Years of Reefer Madness (Part 2): From Nixon to Trump

From Yippie to Yuppie: ’60s Activist Jerry Rubin

Book Review: The Hunt for Timothy Leary