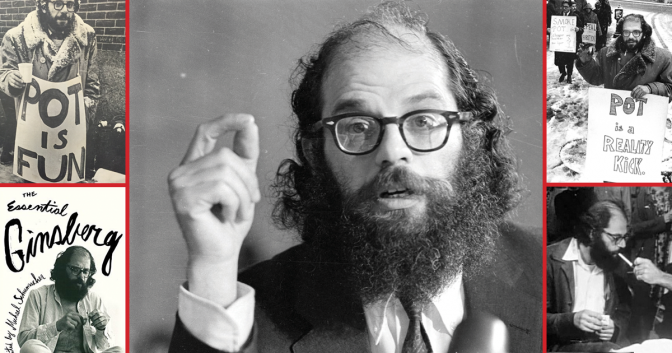

Allen Ginsberg: Marijuana Legalization Pioneer

Controversial beat generation poet Allen Ginsberg was an avid marijuana advocate who helped found the legalization movement.

The first time he was ever really high on marijuana, Allen Ginsberg was driving in a car with Walter Adams, a friend from Columbia University, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. He began to realize how high he was because the streets and people were mutating into some vast robot megalopolis that seemed to be inside a great firmament of brilliant blinking lights, and he began to feel that he was floating in a boundless universe.

At first he was frightened by how fast and radical the changes were in his perception of space and time. He felt hopelessly lost in a place he knew well, and just parking the car seemed a titanic trial. When they finally got the car squared away and walked into an old-fashioned ice cream parlor at the corner of 91st and Broadway, they sat down at a table and he ordered a black-and-white sundae. When it appeared—“this great mound of snowlike ice cream but absolutely sweet and pure and clean and bright”—he couldn’t quite believe his eyes, but as good as it looked, that was nothing compared to what happened when he took his spoon and put some into his mouth. The hot chocolate syrup had become a chewy candy in the ice-cold vanilla cream, and each and every delicious molecule of it seemed to detonate on his tongue.

“What an amazing taste it had! I don’t think I ever truly appreciated what an outstanding invention a black-and-white ice cream sundae was—and how cheap it was, too!”

And then, as Ginsberg perceived the infinitude of the blue sky and looked out the plate-glass window and saw the river of life flowing past—the people walking dogs, smiling, laughing, weeping—he experienced a moment of profound synchronicity and well-being, “everything just perfectly joyful and gay.”

Marijuana had been way more fun and interesting than Ginsberg had ever expected, and he began to think about how he might apply the high to other experiences. At the time, he was taking an art course at Columbia, and he became curious to see what would happen if he experienced the paintings of Paul Cézanne at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in that state of mind, so he arranged a special viewing and made sure to smoke a few “sticks” in the garden before going in. As he stood staring at the paintings, he noticed that he began to understand the artist’s use of space and color in a way he hadn’t before— the way the warmer colors seemed to advance toward him and the cooler colors receded. It was a new kind of funhouse “optical consciousness” that Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac would later call “eyeball kicks.”

One can easily recognize, in Ginsberg’s experience of that black-and-white sundae, a foretaste of the gastronomic delight that millions would later discover after smoking and getting “the munchies,” and reaching for that pint of ice cream, or, in his notion of “eyeball kicks,” the aesthetic foundations of the psychedelic light shows of the 1960s.

But, of course, all of that was decades away. Very few people smoked marijuana at the time, and when Ginsberg would get high and walk around the Columbia campus by himself, he was always acutely and uncomfortably aware of being the only one in that population of 20,000 “intelligent scholars” who happened to be in that particular state of consciousness. In addition to the “fear and trembling that would come just from the sense of being in awe of the great enormity I was in, just in smoking it and altering the mind and being in the universe,” he began to understand the “just plain paranoia that was connected to exploring the illegal unknown…. Remember, there was always the association of what society was laying on you, the notion of the ‘dope fiend.’ If you altered consciousness, there was something wrong with you, and I would often find myself pondering the official terminologies and implications of just what it meant to be a fiend, which is a very strange, horrific, almost science-fiction distortion of reality, wicked and diabolically cruel.

By far what disturbed Ginsberg the most was realizing how this substance that could expand his awareness and actually impart something educational had been so demonized by “this giant official government propaganda machine called the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, because you found it in the media everywhere you looked.”

But as intensely aware as Ginsberg was of the kind of trouble he could get into, that wasn’t about to stop him—“what it had to offer far outweighed the dangers, it seemed”—and that was when he, William S. Burroughs and Kerouac began putting Benzedrine in their chewing gum, and smoking marijuana when they could get it, and going down to Times Square just to see what would happen.

Neal Cassady’s arrest for three joints in San Francisco in 1958 and the suppression of Burroughs’ Naked Lunch were clarion calls that foreshadowed all of Ginsberg’s activism of the ’60s. Before Cassady’s arrest, Ginsberg had only written about drugs; now he began speaking out about them publicly, using his fame as a poet to publicize his views. He also recognized the necessity of informing his opinions with fact, and began compiling his legendary drug files: “I began the files when the Beat Generation first started becoming a public matter—and that included the aspect of drugs and the distortions of the drug story as well as the distortion of the Beat Generation.”

Besides Cassady’s arrest, the other event that turned Ginsberg into “the original culture warrior for cannabis, a one-man anti-reefer madness wrecking crew determined to shake the foundations of pot prohibition,” as Smoke Signals author Martin A. Lee calls him was his 1961 appearance on the John Crosby talk show on CBS TV, along with guests Ashley Montagu and Norman Mailer.

“We were going to discuss the modern sensibility and maybe a touch of ‘Beat’ or ‘hip’ and what it meant on television. I had lunch with Mailer before, and said that I’d like to bring up the subject of the decriminalization or legalization of marijuana. He said that it would be foolish because we’d never get anywhere with that; it would just be considered shocking. But I did say something about it when it came up on the program, and when I did Ashley Montagu added that he thought I was right, there was no great danger with marijuana, and that he thought the government’s story about it was wrong. So then Mailer chimed in that he had ‘tried it somewhere’ and that it was all right; and then Crosby, the host, added that he had tried it in Africa safely, and we all came to this consensus.”

The FCC immediately intervened and forced Crosby and CBS to run a seven-minute refutation from the Narcotics Bureau that denounced the guests for their views. Both Ginsberg and Crosby were enraged by the disavowal, which was run by the network as a public service announcement. Did not a citizen’s right of free speech also apply to the kind of public discussion of marijuana on television he had engaged in?

“What outraged me most was, first of all, the presumption of the government to take over the airwaves like that—they couldn’t do that now,” he said years later. “What right did the FCC have to be opposing our suggestions about the change of a law? But in those days, people were scared to death of the very subject, which is why Mailer had been so hesitant and dubious about even bringing it up. He smoked marijuana and had a lot to lose by the scrutiny of that aspect of his life—just like the rest of us—so it wasn’t only a matter of censorship; it was a matter of the kind of fear, which produced self-censorship, and it was enormous. It was censorship to the extent that you couldn’t even open up your mouth on television without being refuted by the government.”

What Ginsberg did next would have an important impact on his life for years to come. “I wrote a long, long letter to Harry Anslinger [commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics], vowing to get him. I called him a disgrace and presented a long catalog of the duplicity and lies that they had been promoting for so many years.”

In essence, the letter was an audacious declaration by Ginsberg of his passionate intention to pursue through political means the legalization of marijuana in the United States. Nobody knows exactly how Anslinger reacted to the missive, or whether or not it caused the FBI to open its long file on Ginsberg. Doubtless the Federal Bureau of Narcotics was not receiving many such letters in those days, and to send one like it was not only a bold but a reckless thing to do, especially if one happened to be a gay Beat poet who smoked marijuana, as Allen Ginsberg was. From that moment on, the bureau and local narcotics police in New York would look for a way to set the poet up for a marijuana bust.

“When I got my Freedom of Information Act material so many years later, I found out that as of the date of the John Crosby broadcast, from then on, any suggestion that marijuana be legalized—by anybody—went into my file. For about three or four years, right around the beginning of the ’60s, if anyone expressed such a notion in public, in any form, it went into my file. So, yes, I had quite a big file. It was quite amazing.”

Ginsberg was already well aware that any organized effort to legalize marijuana in the United States would be a difficult struggle that would have to be waged on many levels. On the one hand, it would have to confront all the scientific, medical and sociological myths regarding the effects of the weed that had been built up since the ’30s, which had become so deeply ingrained in the public mind that they were blindly accepted as truth by an overwhelming majority of the American population. On the other hand, it would also have to counter what the weed had come to represent in the public mind, and in this regard it would have to deal with an image. This part of the campaign would have to be, in effect, a public relations campaign designed to counter what Ginsberg believed was 30 years of disinformation—to remove precisely what New York Times book reviewer Gilbert Millstein had called its “readily recognizable stigmata,” and thereby make its decriminalization and legalization more plausible.

As Ginsberg viewed it, as surely as Gandhi had to confront the British imperialist mindset in order to bring about the independence of India, such a movement would run headlong into the ramparts of some of the basic premises of American culture, society and politics. Already, by the late ’50s and the coming of the Beat Generation, the notion was being circulated that marijuana was not only harmful in itself and would lead to harder drugs, but that it could induce a “defeatist” sensibility in the population regarding the Cold War. People all across the political spectrum believed that marijuana could sap the will of the people to resist Communism as easily as it could devitalize the will and ability of Americans to work and produce and consume goods and services, which, in a rapidly expanding economy of automobiles and household products would be equally catastrophic— the true undoing of the American way of life.

The files that Allen Ginsberg began compiling, which would eventually become a significant part of his personal archive in the Butler Library at Columbia University, were composed of innumerable yellowed clippings of newspaper articles, carbon copies of reports and dog-eared, underlined studies and oral testimonies—anything he could get his hands on having to do with not only the culture of marijuana, but all the drugs of the illicit pharmacopoeia. If he saw a newspaper article about somebody—like Cassady—given an outrageously draconian prison sentence for a tiny amount of marijuana, he clipped it; any information he could find, any evidence of the skullduggery of the government, the corruption of the police, the machinations of politicians, the inaccuracies of the media, the manipulations of scientists and researchers, was gleaned and gathered, organized and filed.

He was particularly interested in people speaking truthfully about their marijuana experiences—people who could tell the true story of its underground use and culture, as Mezz Mezzrow had done in Really the Blues, and could describe the short- and long-term effects.

Nothing like an independently compiled sociological record of marijuana use had existed in the United States since the La Guardia Committee Report of 1944, which had become almost impossible to locate. Little else existed apart from isolated fragments about cannabis in the scholarly and medical literature in some university libraries; information compiled on individuals by narcotics squads; some intelligence about smuggling and records of arrests in police departments; and the self-serving statistical data of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

What began to accrue in Ginsberg’s East Village pad toward the end of the ’50s, first in manila folders, then in cardboard boxes, eventually in big iron filing cabinets, was a remarkable record of the government’s suppression of a part of its population that would only grow progressively larger over the years—the counterweight to the lies and myths that Anslinger had compiled to launch the crusade against marijuana in the ’30s.

“Almost everyone has experimented with [marijuana] and tried writing something on it. It’s all part of their poetic— no, their metaphysical—education.” As Ginsberg saw it, drugs were going to be “a cutting-edge issue—one of the fundamental ways we defined ourselves as a people in the second half of the 20th century.”

Allen Ginsberg always viewed the Beat Generation as a “decisive moment in American consciousness.” As he fulfilled his destiny as an epic bard and became one of the most famous American poets of the 20th century, he remained focused on drug use and how it could affect consciousness, creativity and culture. He also remained a passionate advocate for changes in drug laws and policies.

On a snowy December day in 1964, Allen Ginsberg made good on his vow to challenge Harry Anslinger and the Marihuana Tax Act by appearing in Lower Manhattan with a small band of activists carrying signs that read “Pot Is Fun” and “Pot Is a Reality Kick.” The group that Ginsberg formed with Ed Sanders was called LEMAR (for “Legalize Marijuana”), and it marked the beginning of the campaign to legalize marijuana in America.

Excerpted from Bop Apocalypse: Jazz, Race, the Beats, and Drugs by Martin Torgoff. Copyright © 2017. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group Inc.

If you enjoyed this Freedom Leaf article, subscribe to the magazine today!